Did you know that Tagalog has the word kila that you won’t find in any textbook, but Filipinos use it every day? And then some other Filipinos directly deny that it exists? But let’s start from the beginning.

Of course, you know that in Tagalog, personal nouns, like names referring to people, such as, I don’t know – Marcos and Duterte – are introduced with case markers. So, it’s:

(1) Si Marcos, si Duterte.

‘Marcos, Duterte.’

If it’s plural it’s:

(2) Sina Marcos. Sina Duterte. Sina Marcos at Duterte.

‘Marcos and others. Duterte and others. Marcos and Duterte.’

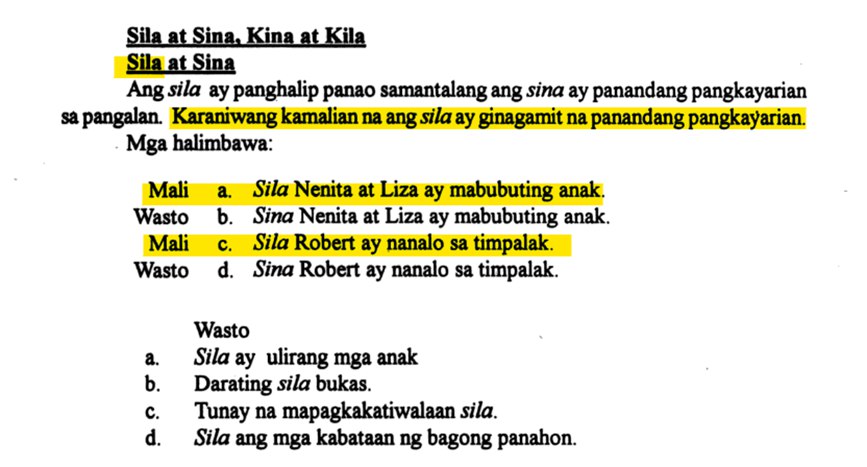

But what you’re not going to be able to find in probably any textbook on Tagalog or most other publications on Tagalog is that you can actually use the personal pronoun here instead of the case marker. So, instead of sina you can say sila, which is the third person plural pronoun (‘they’), like in:

(3) Umalis sila.

‘They left.’

So, instead of saying the phrase in (2) with sina, you can say the same with sila:

(4) Sila Marcos at Duterte.

‘Marcos and Duterte.’

You can hear this use of sila instead of sina every day in the Philippines. It’s everywhere you go. To give you some other real-life examples:

(5) Sikat pala sila Rizal at Bonifacio sa mga taga-Southeast Asia.

‘Rizal and Bonifacio are famous among Southeast Asians.’

(6) May chemistry sila Piolo Pascual at Lovi Poe.

‘Piolo Pascual and Lovi Poe have chemistry.’

And it’s not just sina vs. sila. It’s a complete paradigm! (I guess I lied before when I said there would be no linguistic terms. Paradigm is just a set of forms in the language where one form must be selected in certain grammatical contexts).

So, we have nila used as a case marker. And we also have this peculiar word kila. So instead of using the case marker nina you can use nila with the same meaning:

(7) Sa bahay nina / nila Maria.

‘At Maria and others’ home.’

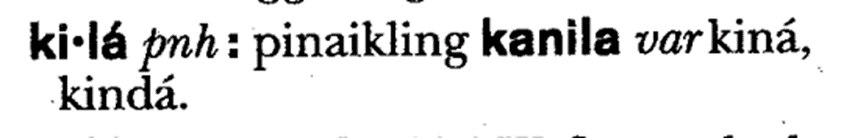

And instead of the case marker kina you can use the word kila, again with the same meaning:

(8) Anong nangyari kina / kila James.

‘What happened to James and others?’

And finally, kila is also used in the predicative form of the same marker, which is used, for example, when we’re talking about location or possession. For instance, you can say:

(9) Sila Felice at Alexei ay nakina / nakila mom and dad.

‘Felice and Alexei are at mom and dad’s.’

And actually, nakila is what you’ll hear more often in the streets.

Is it a recent development?

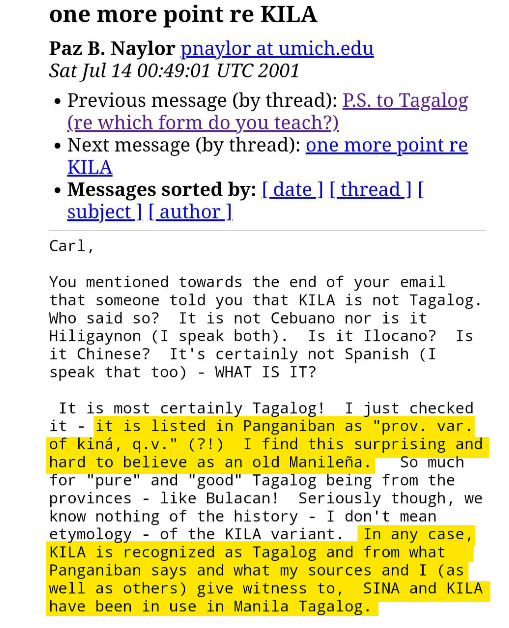

According to the late linguist Paz Buenaventura Naylor, who talked about this to another linguist Carl Rubino on the LinguistList message board in 2001, these forms – sila, nila, kila – have always been used in what she refers to as the “old Manila Tagalog”, or at least since Spanish times.

So, there is no basis to claim that these forms are a recent development of the modern Manila dialects of Tagalog. And although it looks like these forms are not taught in schools across the Philippines to speakers of other Philippine languages (or are they? I can imagine a situation where the teacher who is a fluent Tagalog speaker uses them, but are there any DepEd textbooks mentioning kila? I doubt it), they are everywhere. They are really widely used by native speakers of Tagalog. Although it does look like the textbook forms sina, nina, and kina are generally considered to be more standard , because if you look at written texts in Tagalog, you would see them more often than sila, nila, and kila, when used with personal names. But if we look at conversational texts in Tagalog, I’d expect to see the alternative forms sila, nila, and kila even more often.

What about dictionaries?

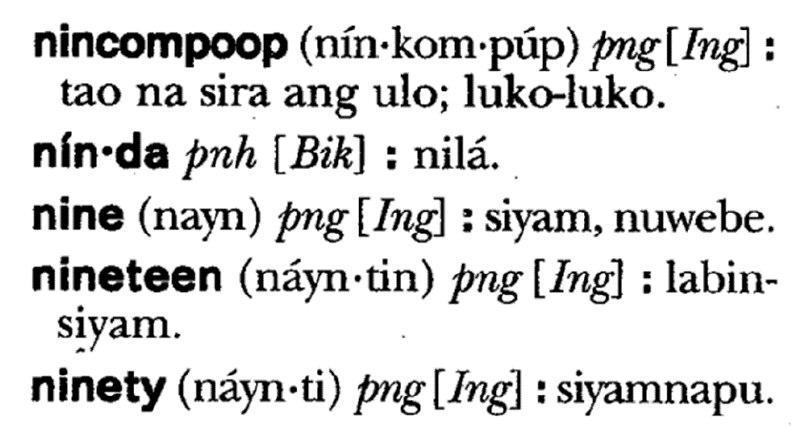

Now, kila is not found in textbooks. But what about dictionaries? According to Naylor, Panganiban’s dictionary lists kila as a “provincial variant of kina”, which, according to her, “surprising and hard to believe as an old Manileña”.

Panganiban is also probably where Rachkov’s 2012 New Tagalog-Russian Dictionary copied it from, as it says that kila is a dialectal form of kina.

Vicassan’s Pilipino-English Dictionary of 1978 lists kila as a colloquial variant of kina.

Another dictionary that I’ve checked – Leo English’s Tagalog-English Dictionary – doesn’t list kila at all.

And finally, the last dictionary I took a look at is Rio Almario’s UP Diksiyonaryong Filipino (this dictionary will highly likely be discussed on this blog in more detail sooner rather than later).

It provides additional information not available in any other of the dictionaries mentioned above. First, it lists another form — kinda — as a variant of kila.

I must say, I’ve never heard kinda used in Tagalog — not a single time! Which, of course, does not necessarily mean that it doesn’t exist. But, the dictionary also lists ninda as a variant of nila — obviously a member of the same paradigm, — labelling it, however, as a Bikolano borrowing.

This borrowing label suggests that Almario and those involved in making decisions on what should be put into the dictionary — in other words, sila Almario — might have listed kinda and ninda solely because they want to see these words as part of Filipino (UP Diksiyonaryo lists countless words from other Philippine languages, words that have never been used in the Tagalog speaking regions and never will. This is in addition to page after page of English words — just look how ninda is lodged between nincompoop and nine, nineteen, and ninety).

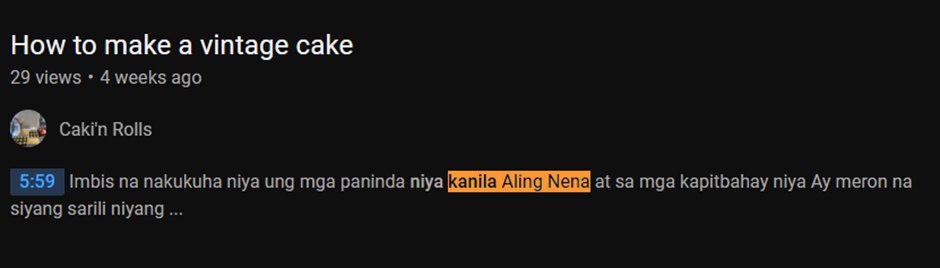

Second, Up Diksiyonaryo also states that kila is a shortened version of the oblique 3rd person plural personal pronoun kanila. It does seem to be a legit use of kanila, since it does occur in the same function as kina/kila as seen from the following examples:

(10) ...nakukuha niya ung mga paninda niya kanila Aling Nena...

'...she gets her goods from Aunt Nena...'

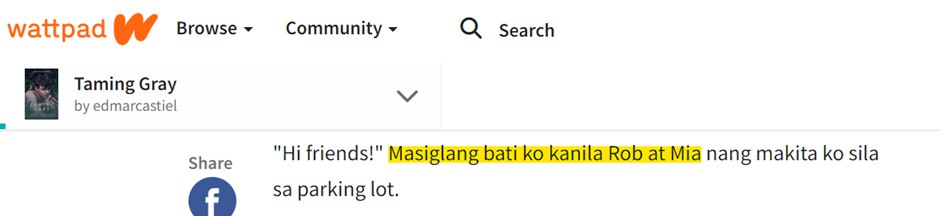

(11) Masiglang bati ko kanila Rob at Mia...

'My cheerful greetings to Rob and Mia...'

However, although I don’t have any figures on the frequency of kina vs kila vs kanila, the latter does seem to be used in this function much less frequently.

As for this special use of sila and nila as case markers, it is not mentioned in any of these dictionaries that I’ve checked.

Denial

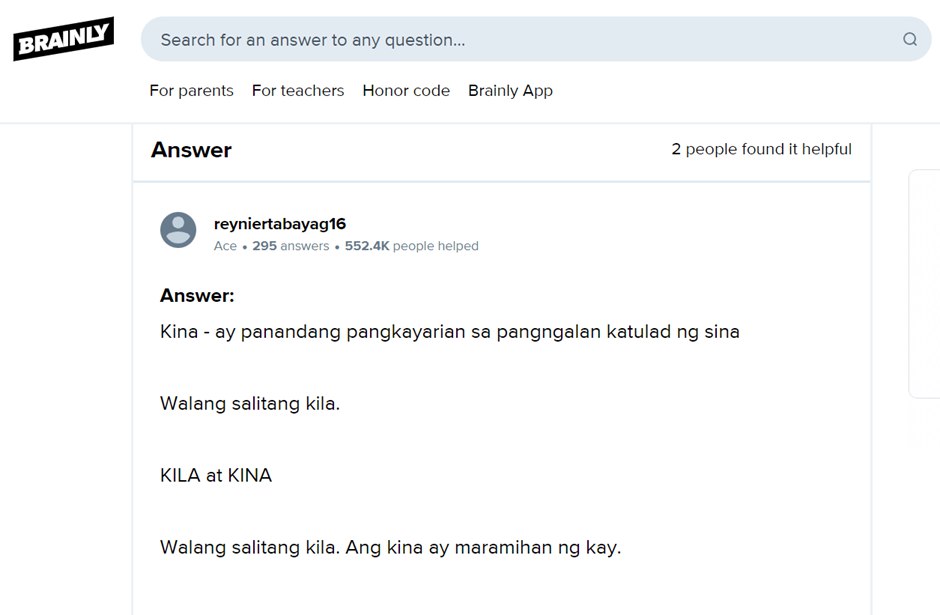

The most amazing fact about kila is that its existence is denied by some Filipinos. Like, people would completely seriously claim that it is not a word that exists in Tagalog. For example, whoever this person is who answered a question on what kina and kila are in Tagalog by saying that there is no word kila.

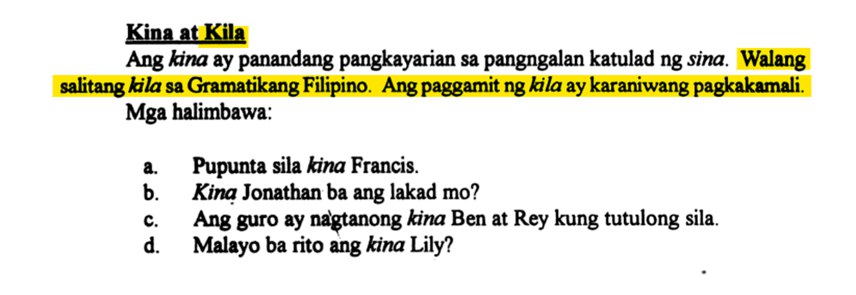

And it’s not just some internet randos who are kila haters. It’s also authors of handbooks on Filipino rhetoric and academic writing.

Example 1. This guide on some “tips and tricks about the proper way of writing” by Emerald Blake, a feature and fiction writer.

According to her, “the word kila doesn’t exist.”

Example 2. This handbook on Filipino rhetoric by Resurreccion Doctor-Dinglasan, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Santo Tomas.

According to her, again, “the word kila doesn’t exist in the Filipino language.”

And example 3. This handbook on rhetoric for the tertiary education level (take a moment to admire this beautiful book cover).

According to these authors, “the word kila doesn’t exist in the Filipino grammar. The use of kila is a common mistake.”

This last group of prescriptivists actually go further and make the same claim about sila – “Using sila as a case marker is a common mistake.”

This rather widespread denial is actually another good reason for linguists to take data obtained from language informants with a grain of salt. Imagine you find an informant who is well-educated and a respected member of the community and they tell you that some things do not exist in their language while in fact they do? Not ideal.

Other Tagalog dialects and Philippine languages

We actually don’t have any publicly available data on this for any other dialect of Tagalog. So, we know that this is pretty common in Manila, but if you come from any other province and speak some other dialects of Tagalog? Is it acceptable in Bulacan Tagalog? In Batangas, Bataan, Marinduque, or other dialects? So, if you’re a speaker of one of the Tagalog dialects outside Metro Manila, what do you think – do you use the same forms, such as sila Pedro, nila Pedro, kila Pedro, nakila Pedro?

It would be interesting to find out as well if this is also possible in any other Philippine language. As of now, I just know that this is definitely not possible in at least some Philippine languages. For example, in Tuwali Ifugao or Yattuka (also spoken in Ifugao province) this is not acceptable. So, in Yattuka, sina Marcos will be:

(12) Di Marcos.

‘Marcos and others.’But, unlike Sila Marcos in Tagalog, you can’t say:

(13) *Ida Marcos.

Intended: ‘Marcos and others.’So, in case you speak any other Philippine language, what can you say? Does it happen in your language?

This is some quite basic stuff. Nearly every Filipino speaking Tagalog knows this and uses this daily. But it is something that’s generally not known to people who learn Tagalog using textbooks or linguistic descriptions. Which is pretty wild if you come to think about it, as Tagalog is the best described Philippine language. It has the greatest number of textbooks, dictionaries, and linguistic publications. And yet, sometimes language educators instead of, you know, educating about the language alienate learners from natural language use by denying existence of such basic and simple things like it’s something to be embarrassed of.

Read about another case of prescriptivist fervor, this time in respect of Tagalog lexical items coined by combining English and Spanish elements here.

Leave a Reply