Glossary

bayanihan: ‘voluntary cooperative endeavor’

bayani: ‘hero’

bayan: ‘town/nation’

bahay: 'house/home'

bola: ‘something said to impress/lies’

I was quite surprised to learn that many people believe the word bayanihan ‘voluntary cooperative endeavor’ to come from the root bayan ‘town/nation’. Why surprised? Because linguistically, it doesn’t make much sense.

I first heard about this a couple of days ago in this recent video (posted on 19 July 2024) by the celebrity historian Michael Charlston ‘Xiao’ Chua on YouTube.

Answering the question “I thought bayanihan came from bayan?”, Chua gave this passionate reply:

“Well, that is what I thought too! Hahahahaha. But I’ll show you something. If bayanihan came from the word bayan, linguistically, it cannot be bayanihan. It could only be bayanan. According to some linguists. So that is why it can only come from bayani. Bayanihan can only come from bayani. And this is also proven by Zeus Salazar using the Austronesian Dictionary. But it’s good. It doesn’t change the meaning of bayanihan. It is still ‘working together’, but not just for the bayan, as it was supposed to, you know, mean. But we working as bayani! That when we band together, when we cooperate, when we unite and solidify with each other to perform a task, to help someone, we are bayanis who are doing bayanihan. And I think that’s even more beautiful and sweet than what we thought it was.”

The idea that bayanihan is derived from bayan is so obviously wrong, because there would have to be a suffix -ihan in order to go from one to the other:

bayan + -ihan = bayanihan

But there is no such suffix in Tagalog! There are no other words that would be formed from their root by being suffixed with -ihan. So, I thought, how common actually is this opinion? Turns out, very!

Web Occurrence

The following examples illustrate how widespread this misconception is.

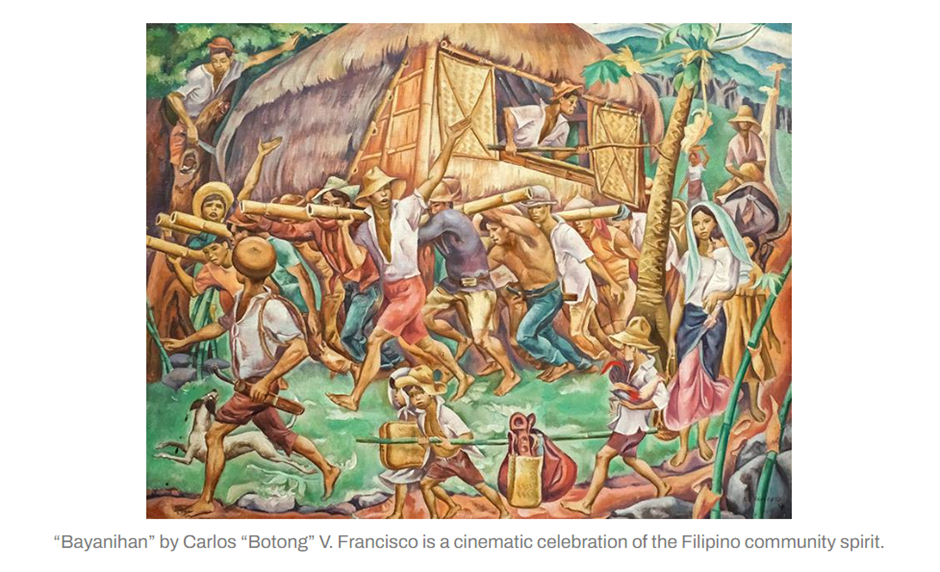

This art auction page discusses Carlos “Botong” V. Francisco’s painting “Bayanihan” this way:

‘…in the work “Bayanihan” he explores the very meaning of the word “bayan” which itself finds its root from the ancient word for “bahayan” or home. A group of houses (or bahay) counted as one would thus comprise a “bayan,” and the man who would be its stoutest and most valiant defender was called a “Bayani.”’

There are webpages like this 50 Beautiful Filipino Words and Their Meanings, where bayanihan is said to literally mean “being in a bayan”. Even though the very next word on the list is bayani, it didn’t occur to the author that they are probably connected in some way?

And here is another example from a “cultural experience blog” making the same claim – that bayanihan is derived from bayan and means “being in a bayan”:

Same claim by the Filipino Bar Association of Northern California:

The Project Bayanihan based at the MIT Laboratory for Computer Science claims that bayanihan means “being a bayan”:

The same claim is also made on the website of a Filipino organisation in the UK:

Another claim of this sort is that bayanihan literally means “being of a bayan”:

The claim that bayanihan is derived from bayan is also found on the Wikipedia page for Communal Work:

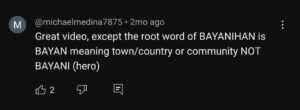

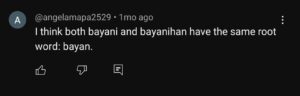

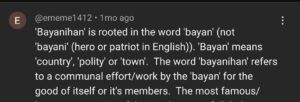

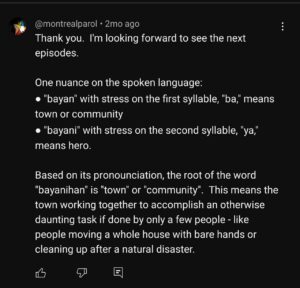

And the same view can be find in comments sections on social media. For example, this YouTube video from the same channel affiliated with Xiao Chua as the one above mentions that bayanihan is derived from bayani. So far, it gathered five comments from different users correcting the authors and saying that it is, in fact, from the root bayan:

Academic Publications

Even more concerning is the fact that the claim about bayanihan being derived from bayan also made its way to academic publications, such as this volume on Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility, which is the source of the Wikipedia page above, suggesting that bayanihan is somehow derived from both bayan and bayani at the same time:

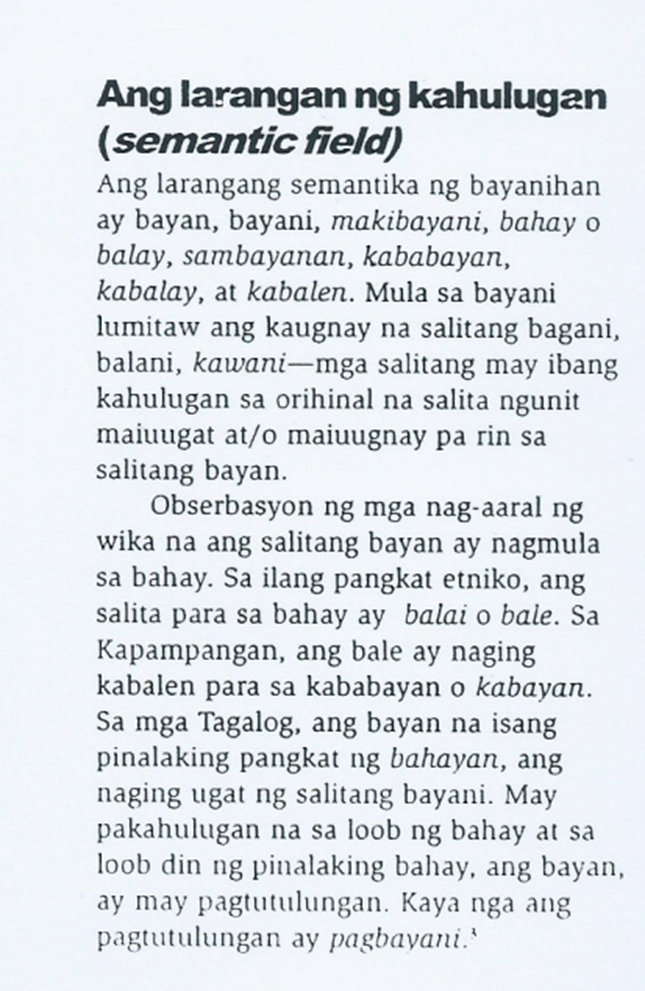

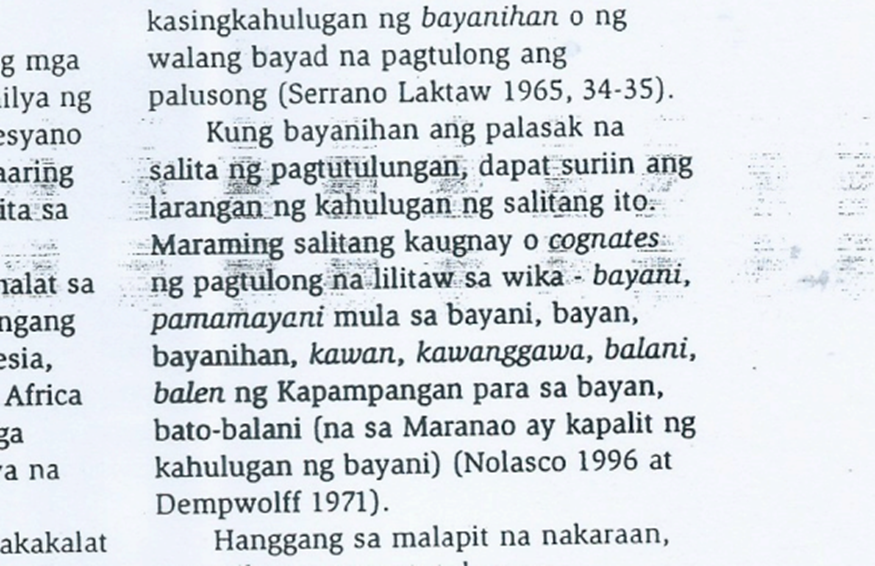

This 2004 paper by Ma. Corazon Veneracion, a professor at the UP Diliman Center for Women’s and Gender Studies makes a claim that bayanihan comes from the same semantic field (whatever it is, since it is not defined by the author) as bayan ‘town/nation’, bayani ‘hero’, and bahay ‘house/home’. It also claims that the Tagalog bayani ‘hero’ comes from the root bayan ‘town/nation’.

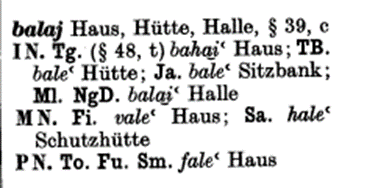

Then Veneracion claims that bayani ‘hero’ and bayan ‘town/nation’ are cognates. But this is a misuse of the term cognate, which refers to words in different languages that come directly from the same word in a proto-language (a hypothetical reconstructed ancestor of actual languages related to each other). For example, the Tagalog bahay, Ilokano balay, Maranao walay, and Itbayaten vaxay originate from the Proto-Malayo-Polinesian *balay. Just like the German Haus and English house are cognates of the same word in a proto-language. When a word is derived from some root in the same language, the two are not cognates.

As you can see from the screenshot above, Veneracion cites two sources for this claim on cognates – Dempwolff’s work on Austronesian word lists and Ricardo Nolasco’s paper on bayani. The problem is, neither work makes any claim on relating bayani to bayan whatsoever!

Around 2007, Xiao Chua himself was touring around education institutions with a talk titled Bayan, Bayani, Bayanihan. But I guess old habits die hard. Because even in the same video with which we started today, – where he says bayanihan in fact is not derived from bayan, – while answering a different question, he says this, still suggesting a connection between bayan and bayani:

“Another way of looking at this is that this is also like the old bayanis from the pre-colonial times. The old bayani goes out of the bayan, they fight and when they go back they bring home dangal. The important items from that bayan, they bring it back home.”

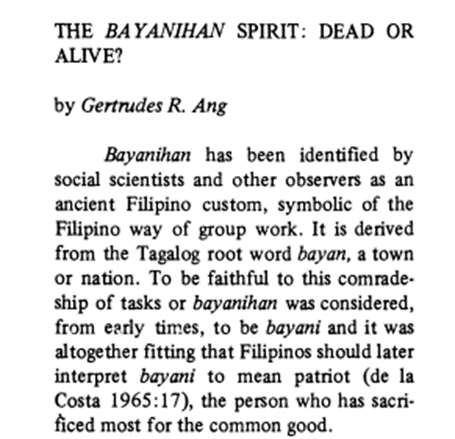

The earliest source I managed to find claiming that bayanihan is derived from bayan is 1979 Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society paper by Gertrudes R. Ang:

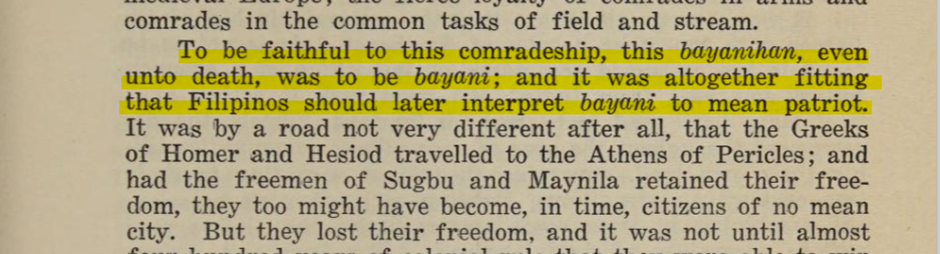

The only reference present in the opening paragraph containing this claim is to a 1965 publication by Horacio de la Costa and pertains only to the claim regarding the interpretation of bayani as patriot.

Are there any earlier sources making the same claim? Was it something that was put in some DepEd materials at some point and taught to generations of Filipino students? Is it some ‘common knowledge’ that people repeat due to bayanihan having a similar phonological structure with bayan and some perceived common semantics (bayan as a community and bayanihan as communal work)? Or did it originate in this paper by Ang? I don’t know.

Dictionaries

Then I thought, well, you don’t really need the Austronesian dictionary (by the way, Chua doesn’t elaborate which dictionary exactly he is referring to) or Zeus Salazar to find out for yourself the root of bayanihan. Because all you need is just a decent Tagalog dictionary.

But then I stumbled upon this 2016 article by another celebrity historian – Ambeth Ocampo – and realized that even a decent dictionary won’t stop people from seeing what they want to see. Ocampo wrote about how he looked up bayani in a couple of dictionaries to find the range of its meanings, but then noticed that it is not too far on the dictionary page from the entry for bayan:

“Bayani in this dictionary has several meanings: someone who is brave or valiant, someone who works toward a common task or cooperative endeavor (“bayanihan”). It is significant that bayani comes a few words under “bayan,” which is defined as: the space between here and the sky. Bayan is also a town, municipality, pueblo, or nation,…”

After which Ocampo jumped to this conclusion:

“I have been opening old dictionaries to find out what bayani meant to people in the past as a way of figuring out what bayani should mean to Filipinos in the 21st century. Johnnie Walker has begun a campaign to help us review and define hero/bayani for our time; it proposes ambition as a peg. That may be one way of looking at the question, but hero and bayani do not have the same meaning. Bayani is a richer word than hero because it may be rooted in bayan as place or in doing something great, not for oneself, but for a greater good, for community or nation.”

I can’t stress enough how the fact that two words are in close proximity to each other on a dictionary page has no significance whatsoever. It is about as significant as the fact that Philippines is next to the entry for Philippi, Battle of (42 bc) in this Oxford Dictionary of World History. In other words, not at all.

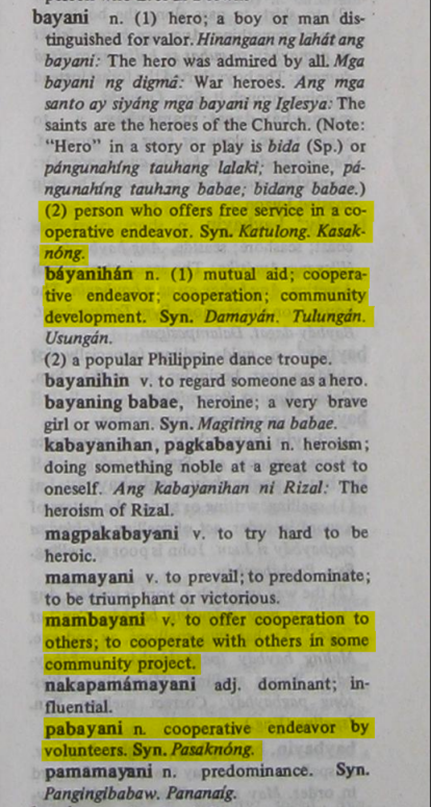

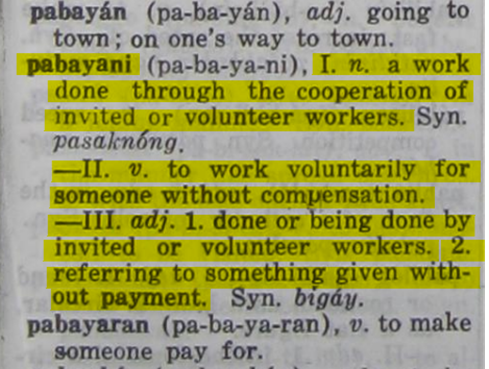

But still, let’s take a look at a couple of dictionaries. For example, this is what we find in Leo English’s Tagalog-English Dictionary: bayanihan is under the entry for bayani, whose second meaning is “person who offers free service in a cooperative endeavor”.

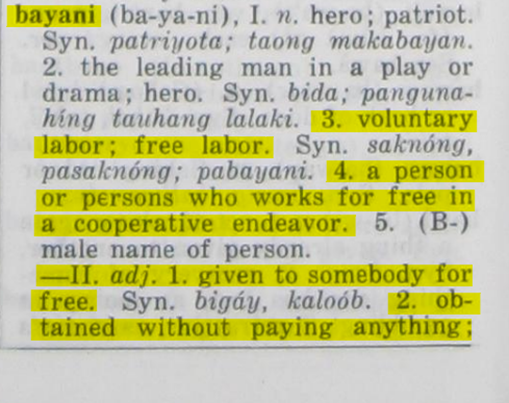

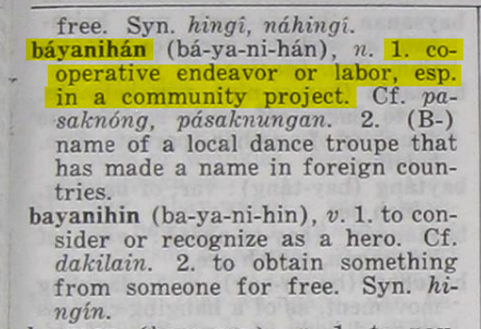

And here’s Vicassan’s Pilipino-English Dictionary, showing several related meanings of bayani: “voluntary labor; free labor”, “a person or persons who works for free in a cooperative endeavor”, “given to somebody for free”, and “obtained without paying anything”.

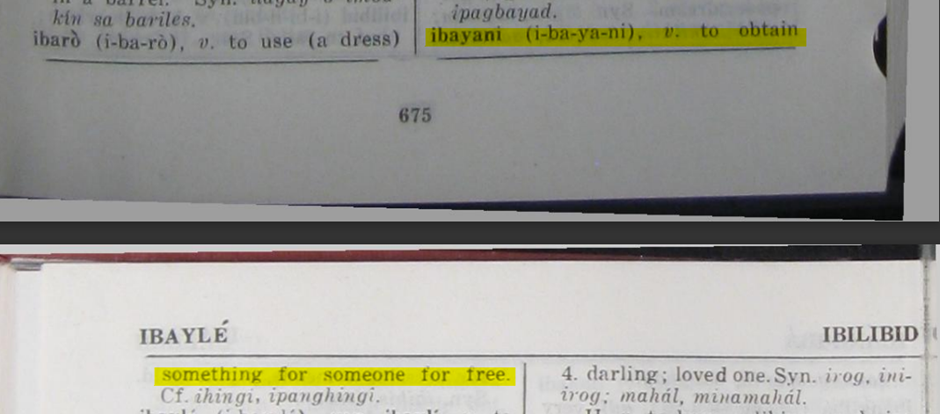

It is also notable that the root bayani with the meaning other than ‘hero’ derives a paradigm that, apart from bayanihan, includes also mambayani ‘to offer cooperation to others; to cooperate with others in some community project’, ibayani ‘to obtain something for someone for free’, and pabayani ‘cooperative endeavor by volunteers’, as seen from the Leo English’s dictionary above and Vicassan’s dictionary on the screenshots below:

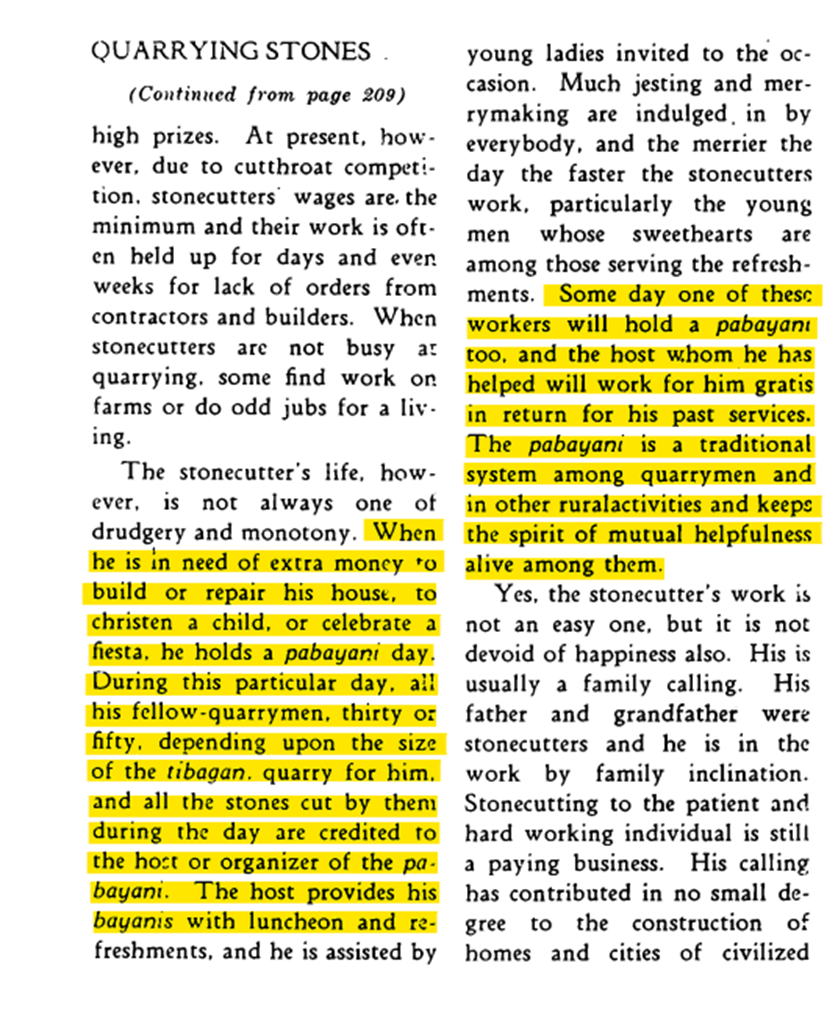

Below is an example of pabayani used in a 1937 publication:

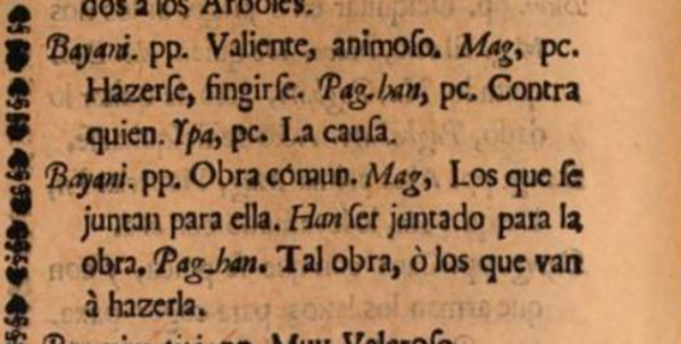

Both meanings of bayani – ‘hero/brave’ and ‘voluntary labor’ – were already attested in the 1754 Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala by Juan de Noceda and Pedro De San Lucar:

Etymology

Speaking of cognates, at present there seems to be consensus that bayani and bahay can be traced back to a proto language as separate lexical items.

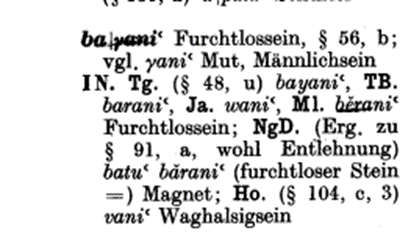

Dempwolff reconstructs two separate forms for bayani ‘hero’ and bahay ‘house’:

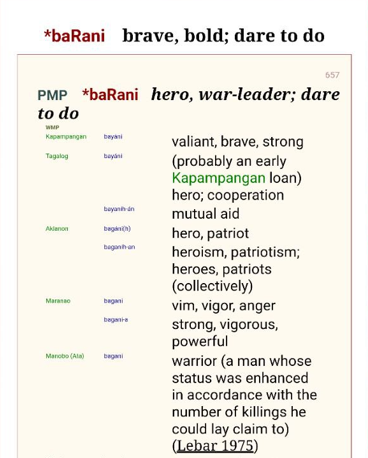

Robert Blust and Stephen Trussel reconstruct *baRani for Proto-Malayo-Polynesian:

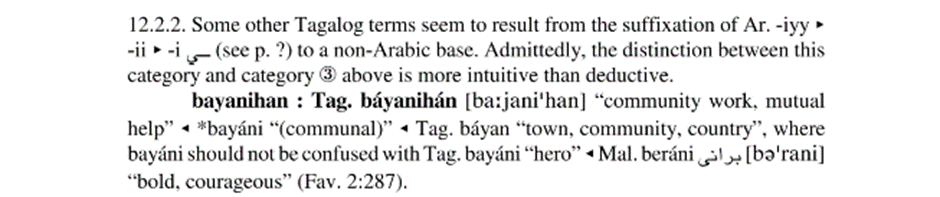

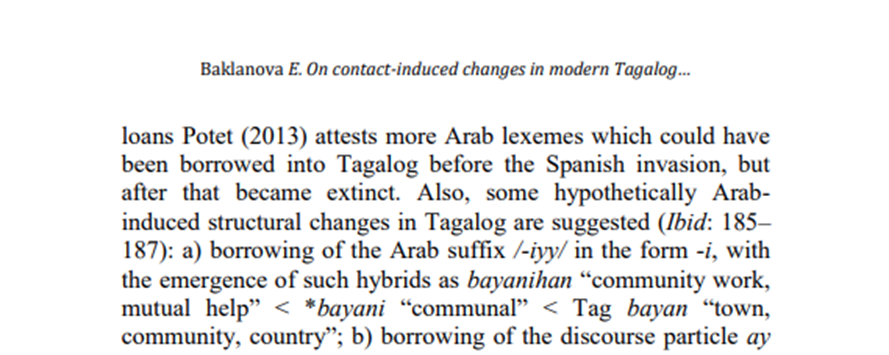

At least one linguist – Jean-Paul Potet (2013) – does claim that bayani is derived from bayan via an intermediate form bayani supposedly meaning ‘communal’ by attachment of a suffix -i purportedly derived from the Arabic suffix -iyy:

This claim is cited in Ekaterina Baklanova’s 2017 paper on contact-induced changes in modern Tagalog:

However, Potet’s claim is problematic, as he does not present any argumentation to support it. Instead of positing a complex derivation involving a non-existing meaning of bayani (‘communal’) and an alleged Arabic borrowing, whose existence needs to be proven separately, it can just as well be hypothesized that the ‘voluntary cooperative endeavor’ meaning of bayani is related to the original meaning of ‘hero, war-leader, dare to do’ through the ‘volunteer’ component. Note how the ‘free’ semantic component of bayanihan is just as important as the ‘communal’ one, as illustrated by Bato dela Rosa’s words “Bayanihan lang walang suweldo” (Translation: “Only bayanihan, no salary”).

Xiao Chua stresses in his video that bayanihan cannot come from bayan, “according to some linguists”. This necessarily implies that there are other linguists who make the opposite claim. Would be nice to have references to their names and works.

In conclusion, I guess relating bayanihan and bayan to each other is ok in creative writing or poetic discourse. This is not to be a gatekeeper to linguistics, but until there is concrete evidence supporting Potet’s suggestion (which might or might not appear in the future), it is inaccurate to claim that it is a linguistic fact that bayanihan is derived from the root bayan, and at the same time it is derived from the root bayani, and so each one of us is like a bayani in our bayan. It is not ok to ground historical reasoning in linguistic fiction.

“Panahon na upang gumising, upang sa ating dakilang BAYAN, dadami ang mga BAYANI na magaganda ang kaluluwa, magkakaroon ng BAYANIHAN tungo sa pagbubuo ng bansang tunay na maipagmamalaki! Malaki ang papel ng kabataang mulat sa Kasaysayan at Kalinangang Bayan.”

Michael Charleston “Xiao” Chua

Translation: “It is time to wake up so that in our great NATION, there will be more HEROES with beautiful souls, and there will be a spirit of COOPERATION towards building a country we could be truly proud of! The youth who are aware of our History and Culture play a significant role.”

It is not ok because it replaces the process of finding verifiable evidence-based pieces of knowledge with wishful thinking limited only by aesthetic desirability. Which undermines any message that a historian, anthropologist, or any other social scientist using this as evidence wants to deliver.

The sort of reasoning linking bayanihan to bayan without any solid linguistic evidence is not unlike to finding the same root in such words as katiting ‘tiny amount’ and titig ‘stare’.

Leave a Reply