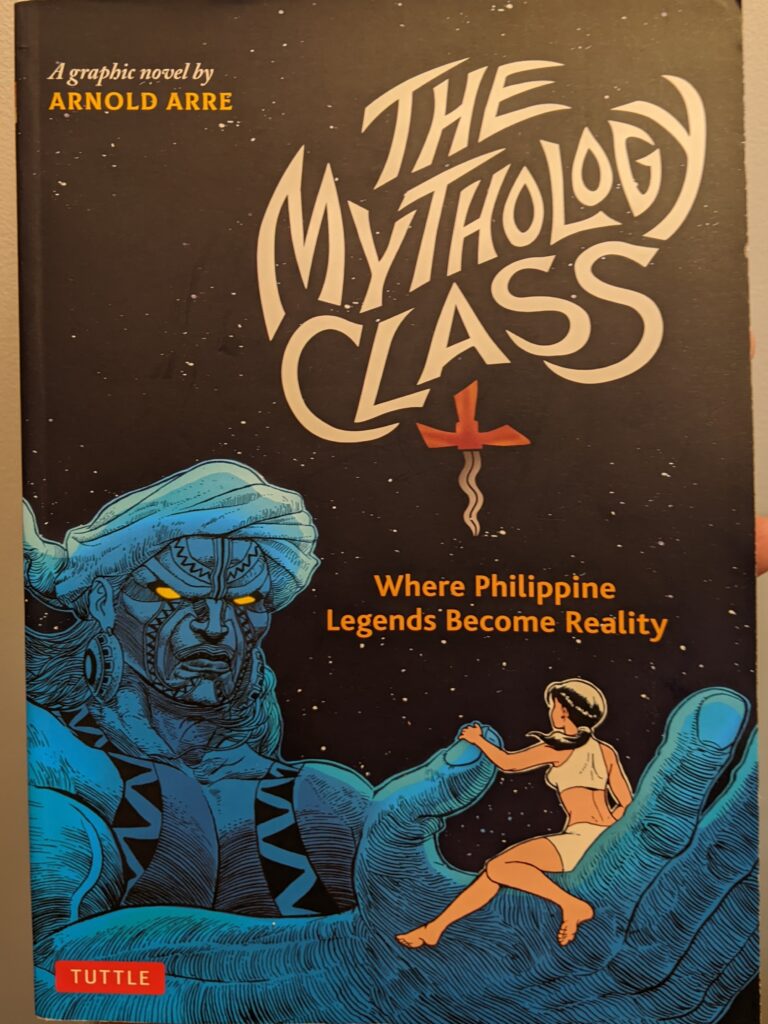

Just finished reading this 1999 graphic novel by Arnold Arre about a group of UP Diliman students who enrolled in a class that turned out to be a recruitment drive for some ancient engkanto hunters.

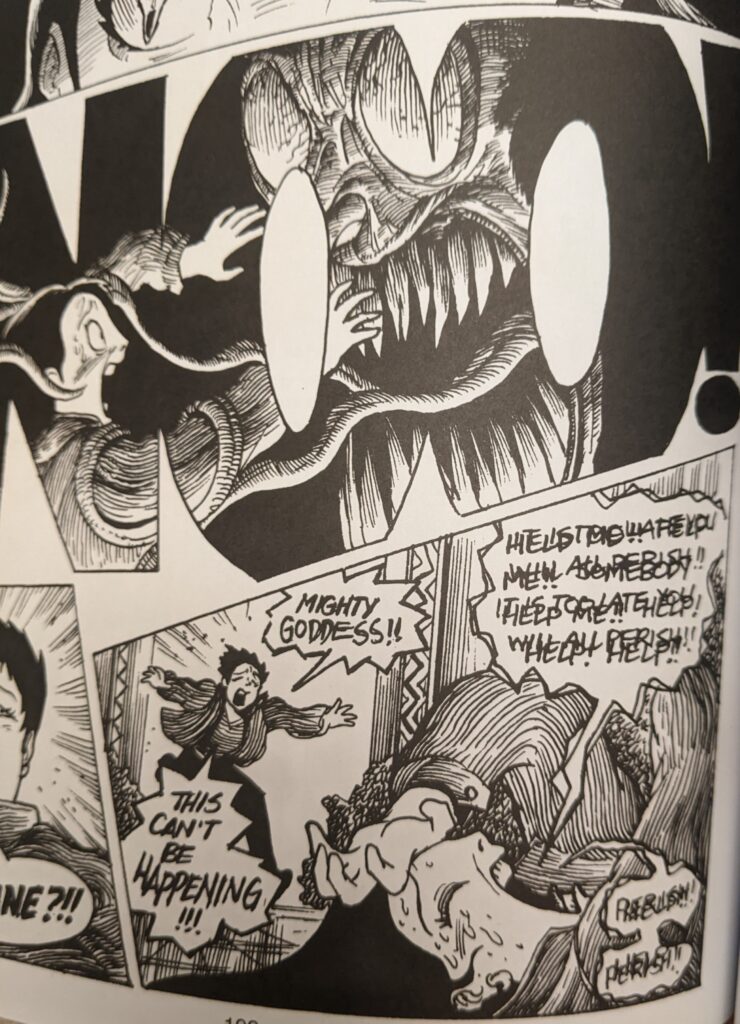

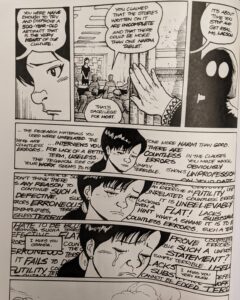

Sadly, I must say that although I was excited to read another Philippine graphic novel (after Gerry Alanguilan’s Elmer, which to me is one of the best graphic novels ever), I am not impressed. Sure, the book’s got a couple of cool things, such as this “double speak” (not sure what else to call it) where two phrases are written on top of each other in the same speech bubble. Maybe, this trick has already been used in some other comic books, but I haven’t seen it before.

Or how aswangs are shown as a pack of silly dogs (in which they turn every morning to turn back to the aswang shape at night), each one with a unique appearance.

But let’s focus on one aspect of this graphic novel that was obviously meant to add to its distinctly Filipino flavor — baybayin.

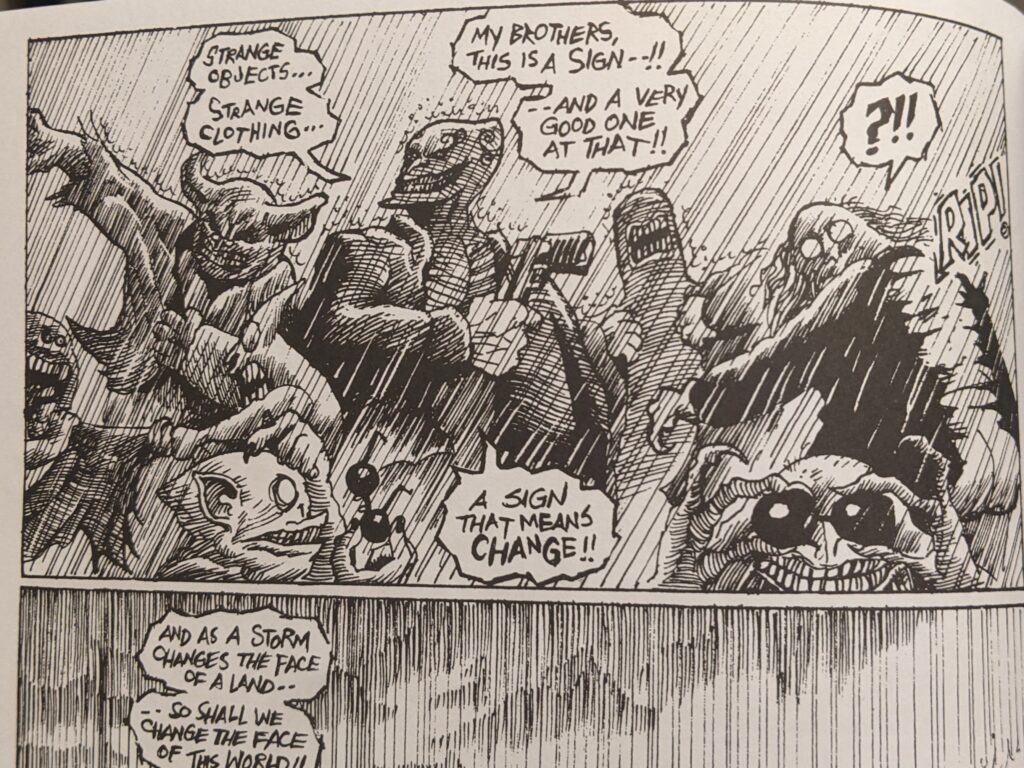

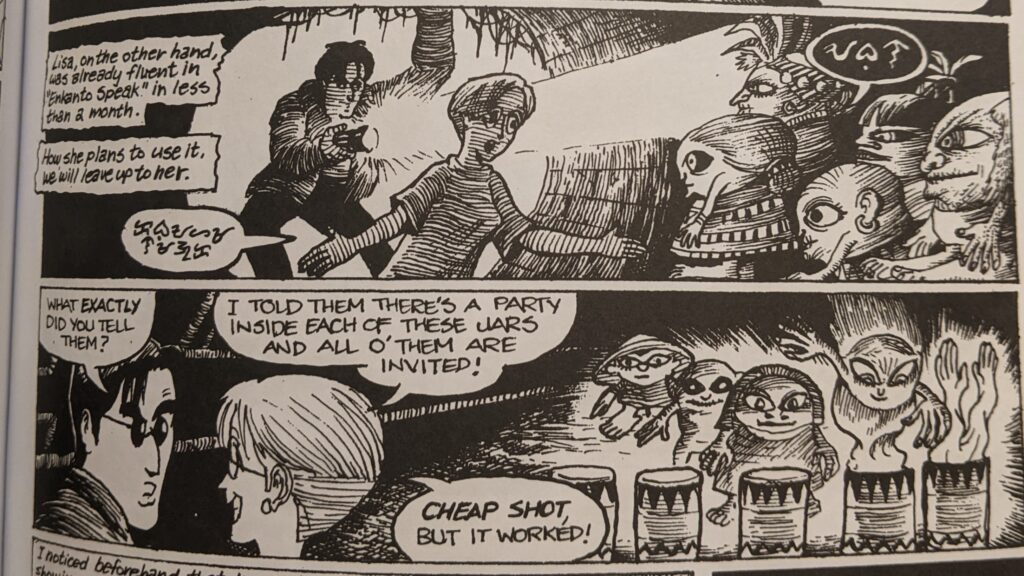

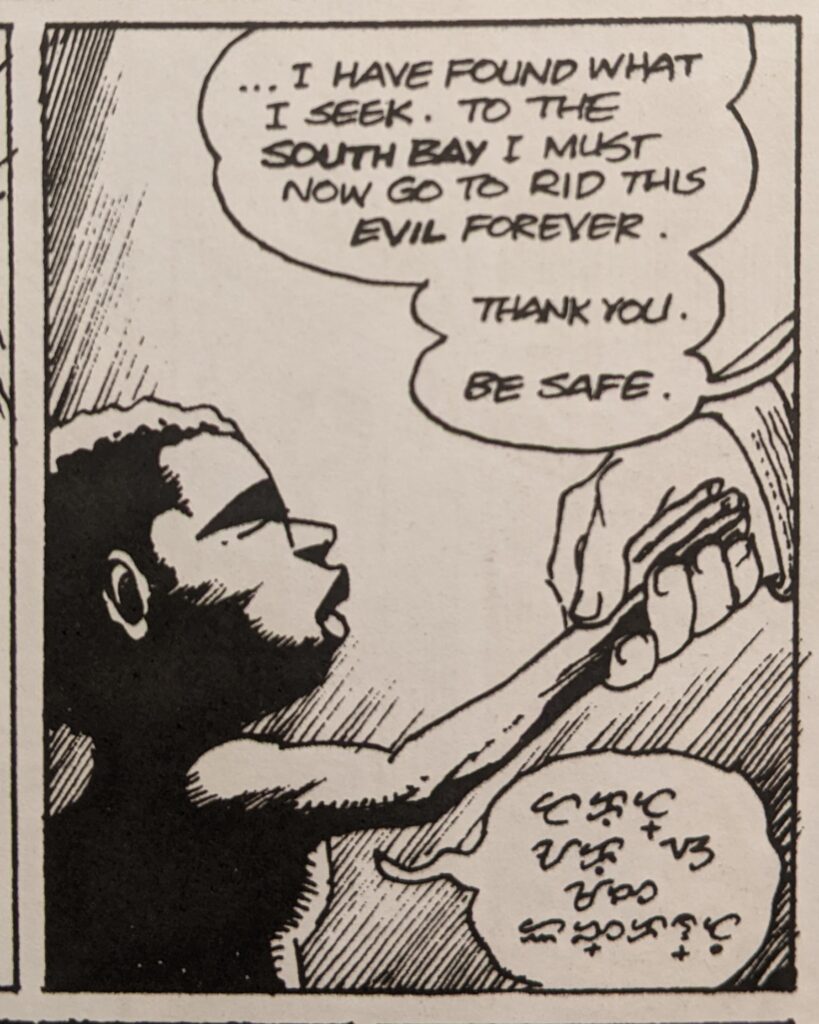

Baybayin in The Mythology Class has a special function. It is used as the “engkanto speak” — most engkantos‘ utterances are written in it (“engkanto” in the story is an umbrella term for all kinds of mythical creatures): tikbalangs, shokoys, kapres, manananggals, etc. All, except the aswangs, a tiyanak, and a nuno, who for some reason only speak in plain English and/or Tagalog. Probably, because what they say is important to the story, which is mostly in English with very minimal Tagalog.

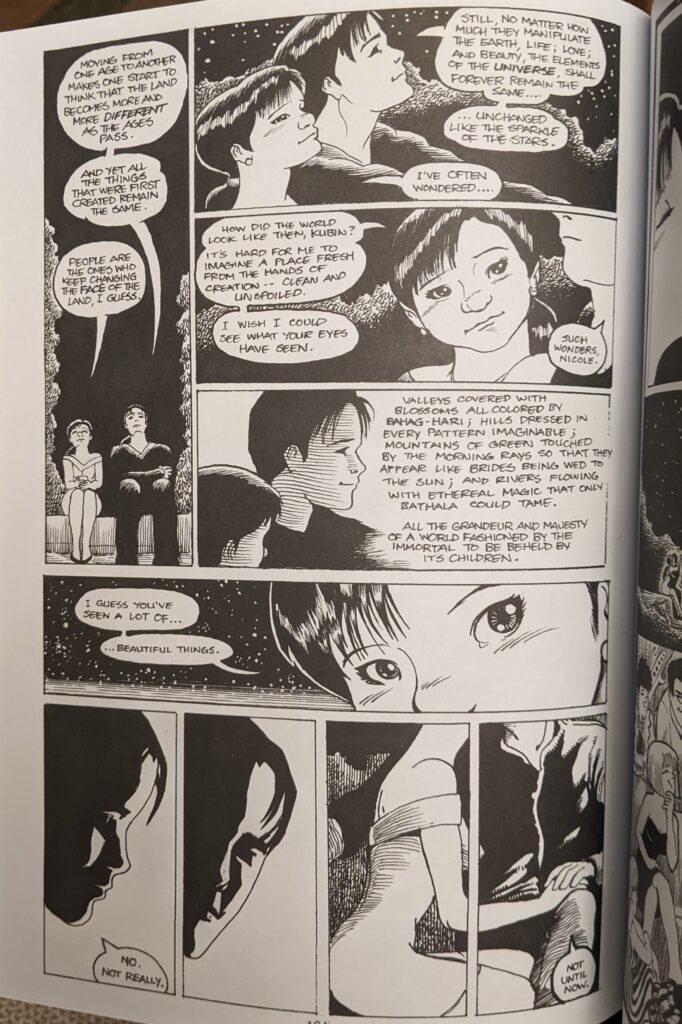

All the ancient heroes featured in the book — Lam-ang, Sulayman, Kubin, and others — also occasionally speak in baybayin — apparently to highlight their mythical and ancient status.

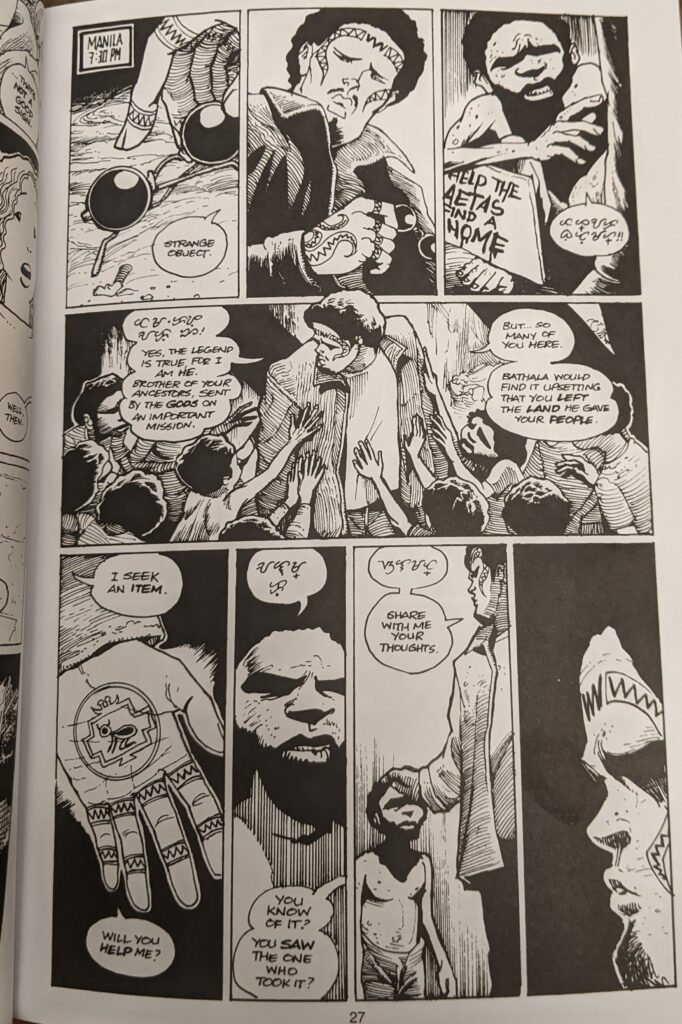

But one group of characters stand out here. Aetas for some inexplicable reason also only express themselves in baybayin! Are they supposed to be some sort of engkantos too?

And why are they speaking to Lam-ang in Tagalog? They’ve got their own languages! Is there any evidence at all that they ever used baybayin?

And sure, Negritos are generally smaller than Austronesian Filipinos. But why did you have to draw them SO small?!

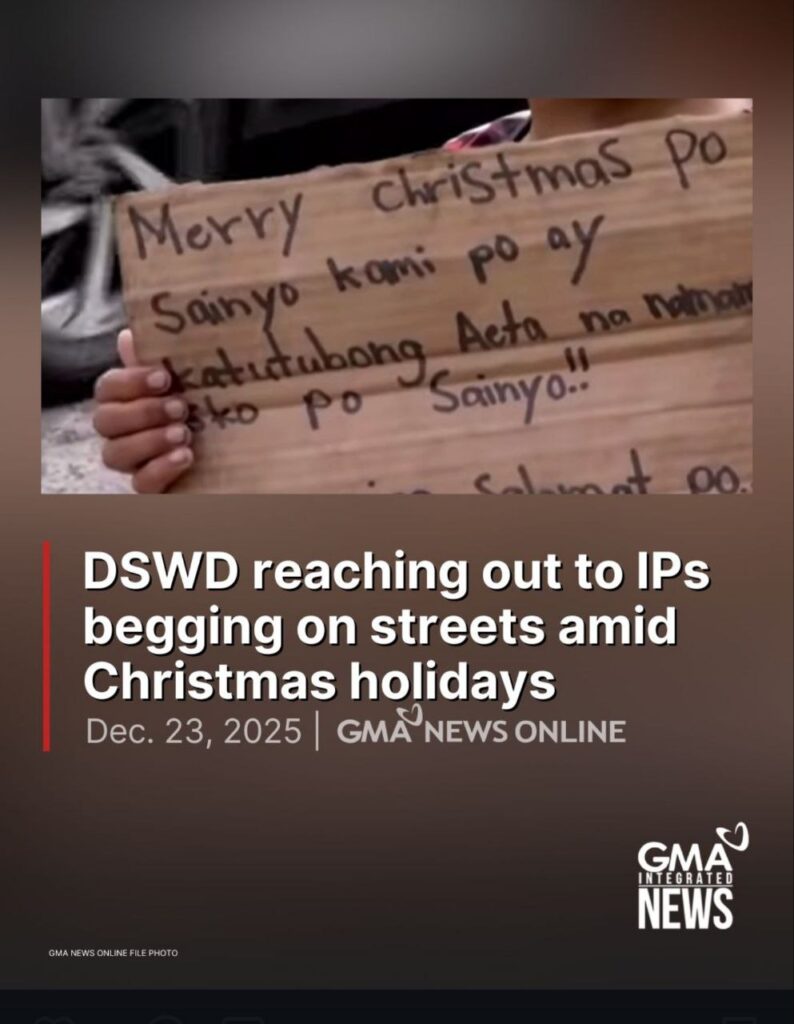

And why the hell are they homeless? Yes, there is an unresolved issue with some Aetas begging in large cities especially over the Christmas season. But why would you make it the sole representation for all the Aetas?

Also, some acknowledgement of the fact that they were initially deprived of their lands by the 1991 eruption of the Pinatubo volcano and now the situation is aggravated by private developer encroachment would be nice. And what’s that comment then about Bathala being upset about them leaving their land? E sumabog nga yung bulkan e.

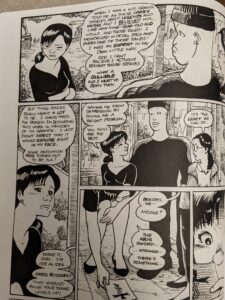

And why do you have to patronize him and read his mind by holding him on the head? He’s a human being, he can literally speak for himself!

Another thing about the use of baybayin. In the world of the book, Bathala, Apolaki, Sitan, and so on are real gods. So, the story is heavily focused on the pre-colonial side of Philippine culture. But the word “engkanto” itself is Spanish! Why would these ancient mythical creatures be using Spanish words?

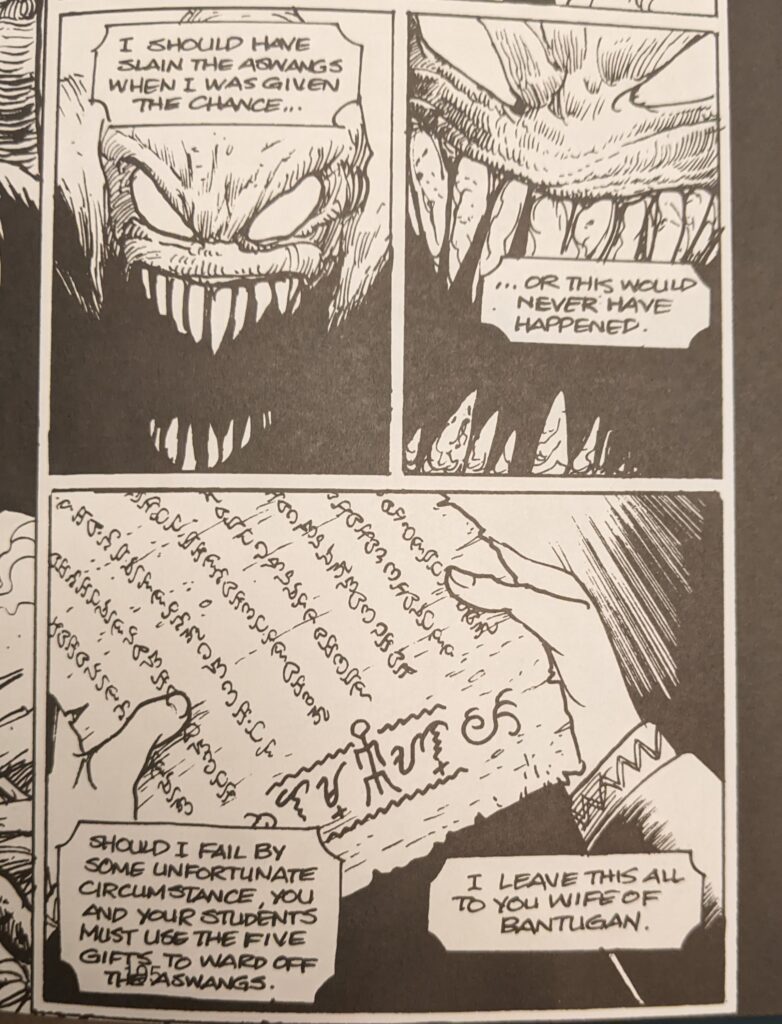

And why is the baybayin spoken by engkantos has the Spanish-era modifications? The cross signifying that the vowel of a baybayin character is dropped (to write syllable-final consonants) was a 1620 invention by Fr. Francisco Lopez, which reportedly was never fully accepted by the natives. Originally, the final consonants were just dropped in writing (Paul Marrow: Baybayin – The Ancient Script of the Philippines).

Also, why is it written vertically in some frames showing ancient artefacts? Is there any solid evidence that baybayin was ever written vertically and not horizontally?

Lastly, seeing so much baybayin in the book, I was excited to grab a baybayin cheat sheet and decode it to see what the engkantos (uhm, and the Aetas) say. But most of the baybayin phrases are just gibberish! Sure, let’s give the author the benefit of the doubt and assume that it might be some other Philippine language, or a representation of the author’s idea of engkanto‘s ancient/otherworldly language. But then some of it is in fact the modern-day Tagalog (there is a lot of “salamats” in the story written in baybayin). And the syllable structure in the frame below is not typical for most Philippine languages.

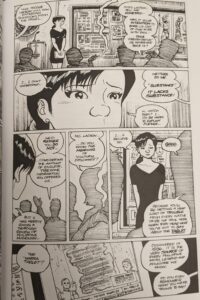

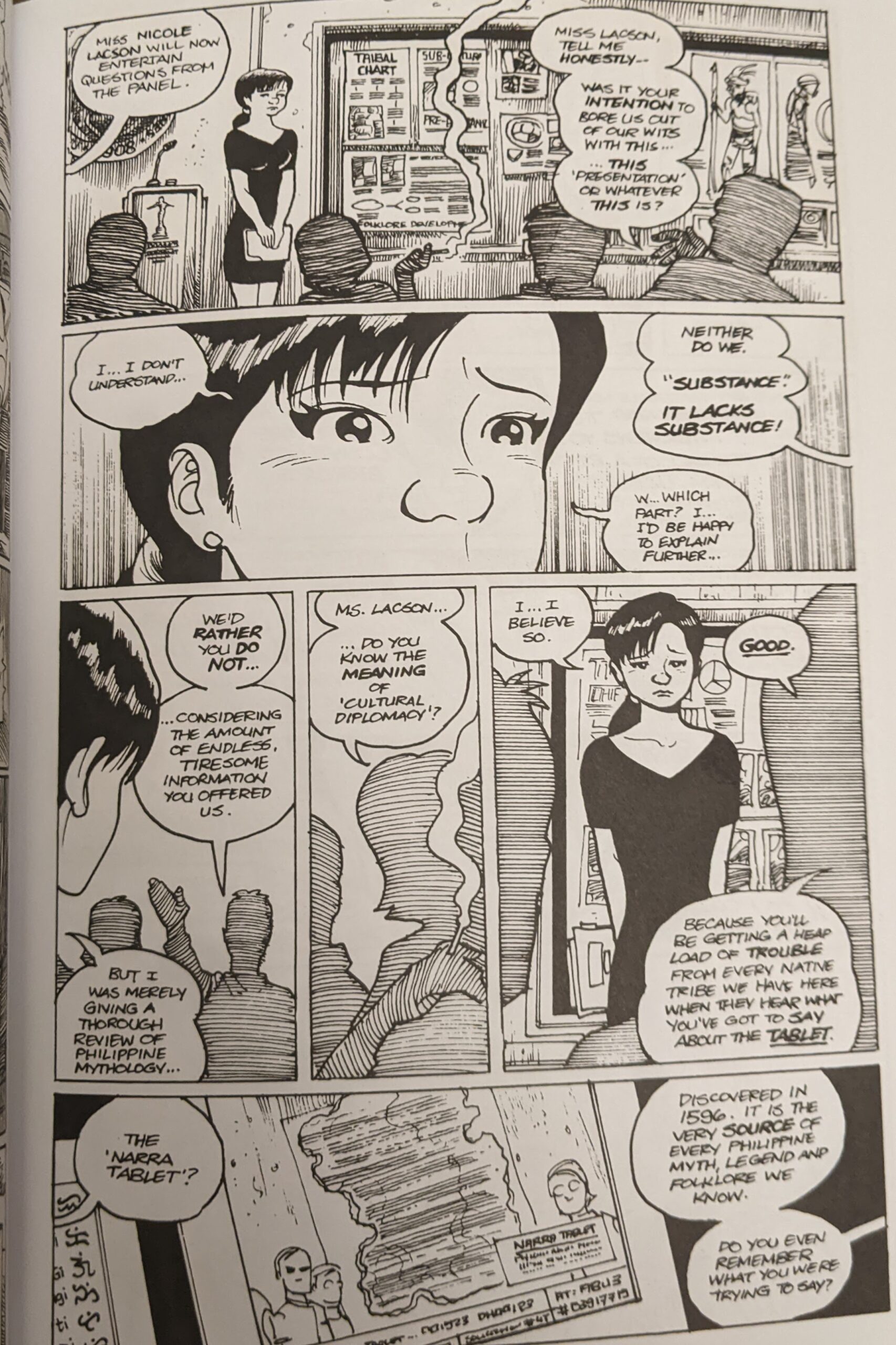

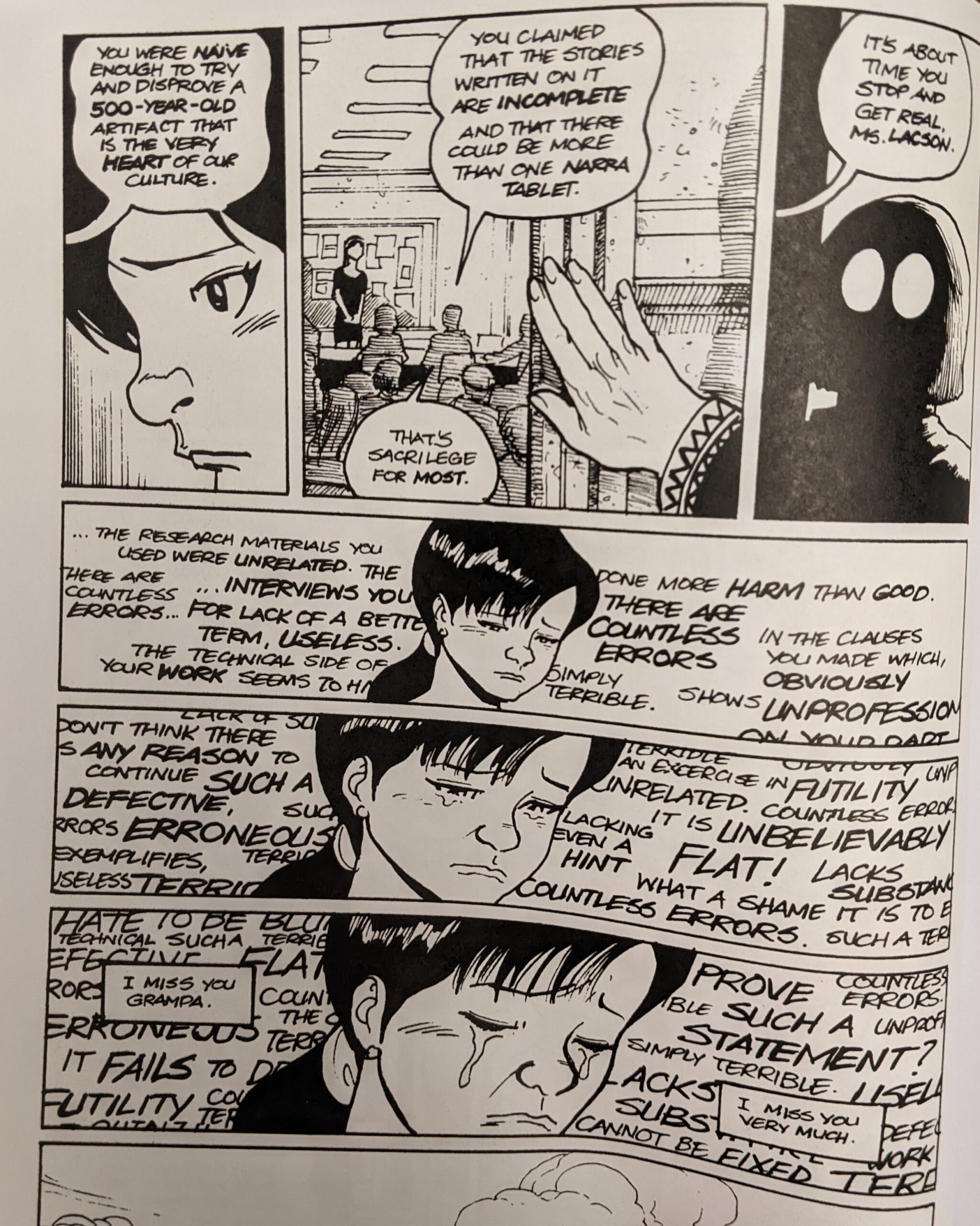

Baybayin is not the only thing in the book that made me cringe. The story starts with this thesis defense scene, which totally misrepresents what the scientific method is and isn’t.

An unreserved belief in validity of the contents of a single ancient text (a fictional “narra tablet”) sounds more like religion. I have never seen an academic who would fail a student just for questioning such a belief.

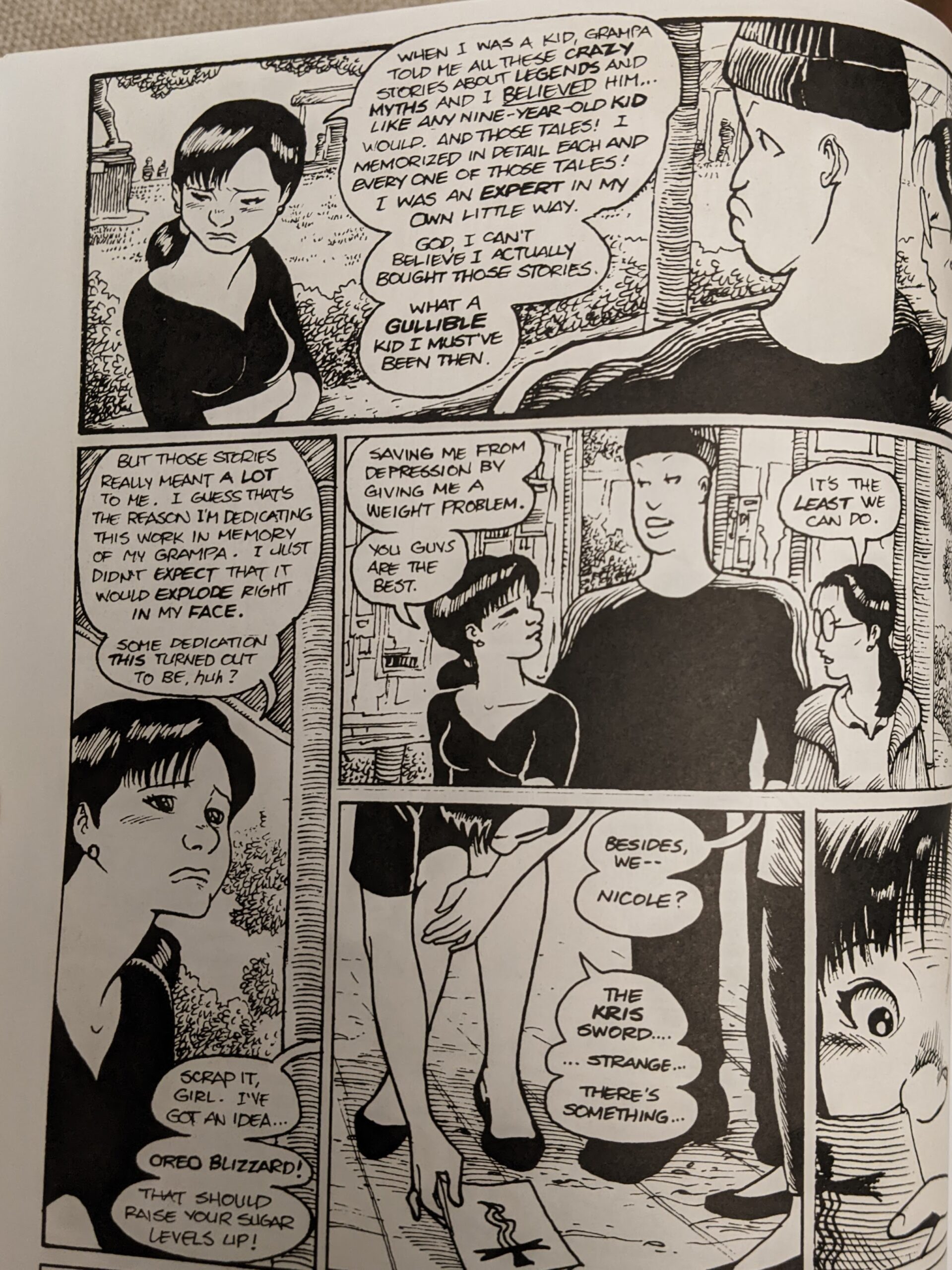

And of course it goes without saying that a student who after four years of college education doesn’t realize that you can’t use your childhood recollections of your grandfather’s ramblings as the main source for your thesis deserves all sorts of reprehension. Like, imagine it was a medical student? ‘You need your appendix removed? Lemme tell you what my gramps used to say about this.’

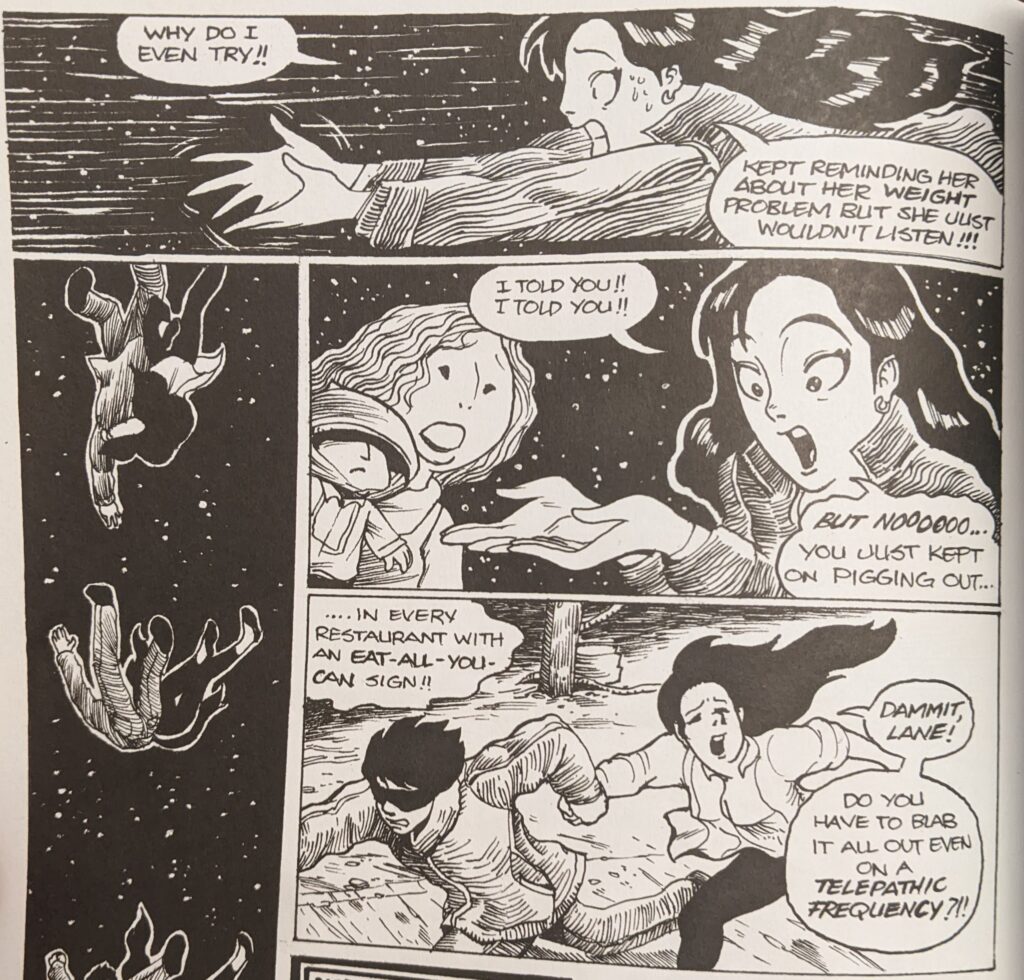

There are also some other issues that leave a stale aftertaste after reading The Mythology Class. It’s got its fair share of the damsel-in-distress trope, you bet. But it’s not just that. The amount of fat shaming here is outstanding. It is remarkably vicious and relentless even for year 1999, which was a much simpler time in terms of political correctness.

Finally, although after watching a scene in Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle with a completely pedophilic vibe, it’s not as impressive to see a romance between a senior college student (what is she, 19-20?) and a centuries-old man, it does raise some ethical questions about this “barely legal” interdimensional fling. Yikes.

Cringe, narrative platitudes, and lots of nonsense baybayin — if that’s your cup of tea, then chances are you’ll love The Mythology Class.

Leave a Reply