In the first two parts of this series we explored the recent political environment and the broader societal context of misogyny in the Philippines in response to one columnist’s claim that Tagalog has no word for misogyny because misogyny is alien to Filipinos. Now it’s time to address the question ‘What is, after all, misogyny in Tagalog?’ The best way to approach this is to look at what Tagalog speakers actually use to refer to this concept. This might look like a rather dull exercise with a pretty obvious answer in the end. But in fact, the answer to this question offers a chance to take a peep into a number of rather exciting issues, such as indigenization of loanwords, incorrect assumptions about data, discourse on prescriptivism vs descriptivism, and diglossia driven by political values. Let’s dive in.

English Borrowings

A very reasonable guess would be that Filipinos just use the English word misogyny, right? And that does seem to be the case. There are plenty of examples of misogyny used in Tagalog texts, both written and spoken, by official organizations, media, public figures, and private individuals.

There is a 2019 video Ano ang ‘misogyny’? (“What is ‘misogyny’?”) in the official YouTube account of the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines.

There is an episode of The GendeRadyo podcast on Spotify has an episode ‘Ano ba ang misogyny?‘ (“What is ‘misogyny’?”)

In 2019, the University of the Philippines Diliman Gender Office had the theme ‘Laban UP! Laban sa Misogyny!‘ – or “Fight, UP! Fight the Misogyny!” – in an event on the International Women’s Day. They even had the same slogan printed on their t-shirts on the day.

In 2017, congressman Antonio Tinio said:

“Kahit dito sa House, matindi ang chauvinism, misogyny ng mga miyembro mismo. Unfortunately, in the case of the hearings kay Senator De Lima, talagang on display publicly yung ganung klaseng behavior. Kahiya hiya para sa akin bilang miyembro ng institusyon.”

Translation: “Even here at the House, chauvinism, misogyny is intense even among the members. Unfortunately, in the case of the hearings on Senator De Lima, this kind of behavior is on public display. It’s embarrassing for me as a member of the institution.”

There are also a lot of instances of the words misogynist and misogynistic in Tagalog speech that one can find online. For example, in 2022, the presidential candidate Leody de Guzman said:

“Nagkataon lang na sa kasaysayan ay may mga significant na mga papel na ginampanan ang mga babae, pero hindi naman ako misogynist. Taga-promote nga ako ng womens’ rights, tagapag-promote ako ng divorce.”

Translation: “It so happened in history that women have played significant roles, but I am not a misogynist. I’m a promoter of women’s rights and divorce.”

In short, despite what Rodel Rodis believes, there is misogyny in the Philippines. There is a word to speak about misogyny in the Philippines. And the word is ‘misogyny’. Sounds a bit boring and uneventful? Yeah, but this is not the whole picture.

Spanish Borrowings

What about Spanish borrowings, are any used in Tagalog as well? You bet. In Spanish, misogyny is mainly misoginia. Mainly, because the Latin American variants of Spanish also have the word misoginismo. For example, the News on the Web corpus of Spanish (7.6 billion words) contains 5,967 occurrences of misoginia – both from Spain and the Americas. But there are also 8 occurrences of misoginismo – all from websites based in the Americas.

Misogynist(ic) in Spanish – as a noun and an adjective – is misogino for masculine and misogina for feminine. There are 221 tokens of these adjectives (including their plural forms) in the same corpus. But, there are also 6 tokens of misoginista, all used as misogynistic and, again, all in American sources.

Now, which of these words have been borrowed into Tagalog? Let’s begin by looking it up in dictionaries.

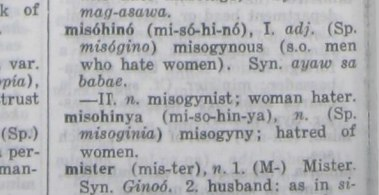

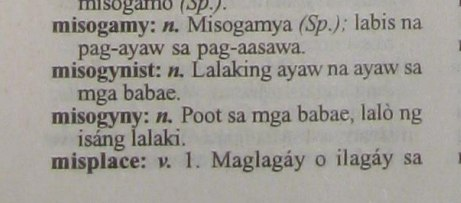

UP Diksiyonaryong Filipino lists the word misohino, right next to misogyny. As usual with this dictionary, it is not clear whether National Artist Virgilio ‘Rio’ Almario, who is the chief editor of the dictionary, believes that these two words reflect the actual usage by language speakers (descriptively) or that these two words should be part of the Filipino language (prescriptively) – the inclusion criteria for lexical entry are not given in any detail anywhere in the dictionary. Either way, there seem to be only three logical options explaining the exclusion of the Spanish misohiniya and English misogynist(ic) from here: i) they are not used by the Filipinos, in the opinion of the dictionary makers, ii) they do not meet the high inclusion requirements set by the dictionary makers, or iii) the dictionary makers just didn’t care (note how misogyny – the phenomenon – is defined as misohino – or the woman-hater).

Vicassan’s Pilipino-English Dictionary (1988) lists misohino and misohinya.

Interestingly though, New Vicassan’s English-Pilipino Dictionary (1995) does not translate misogynist and misogyny with the Spanish borrowings but defines them periphrastically – as “a man who hates women” and “hatred towards women, especially by a man”.

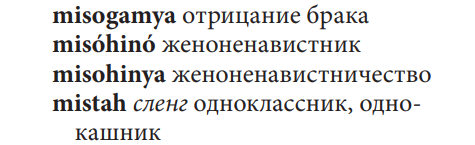

Rachkov’s New Tagalog-Russian Dictionary (2012) also lists misohino and misohinya.

Panganiban’s Consice English-Tagalog dictionary (1994/1969) and Leo English’s Tagalog-English Dictionary (1986) and English-Tagalog Dictionary (1965) don’t give any misogyny-related entries.

Looking at the actual usage, there are not so many googleable instances of Spanish borrowings for the words misogyny and misogynist(ic). Some of them are potentially instances of automated translation, and hence not valid data for our exercise here. For example, the Tagalog Wikipedia page for misogyny says misohinya, but it seems to be a direct translation of the introduction of the corresponding English page, which is sometimes a strong indicator of it being a product of automated translation. But we definitely can find a handful of legit uses of this word online as well.

For example, misohinya is also used by some Cristina Catbagan in her piece in Amianan Balita Ngayon, posted on March 9, 2024.

A tweet by UP Socius, a sociology student organization at the University of the Philippines Los Banos, uses the same word, but spelled with an ‘iya’ at the end – misohiniya.

Same word – misohiniya – is used in a paper Si Judith Butler at Kasarian ng kasarian by Louie Jon A. Sanchez’ – a poet and an associate professor of broadcast communication at the UP Diliman in a collection of articles titled Ang imahen ng Filipino sa Sining.

Now, what about misogynist(ic)?

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the 11th Philippine Linguistics Congress held at the University of the Philippines in 2011, Moreal Nagarit Camba used the word misohino:

A 2022 Rappler op-ed speaks of “misogynists scared of our capability”.

A podcast episode by Malik-Laya (arts and design students at St. Paul University Manila) talks about kultura ng macho at misogino “macho and misogynist culture” in Philippine art.

Interestingly, blogger Leo Fordan – a University of the Philippines Baguio student at the moment of writing his blog – claims that the word misohino would sound weird to any native speaker, and that the word that’s actually used in Tagalog – as observed in activists’ speech, according to him, – is misoginista.

As you can see from the misohino examples above – and as often happens with the language – one native speaker’s “weird” is another native speaker’s “just fine”. But Fordan is right about misohinista – it does have occurrence in the actual usage. So let’s take a look at some examples of the Latin American Spanish borrowings in Tagalog texts.

Bayani San Diego Jr. in his 2018 Philippine Daily Inquirer review of Lav Diaz’s movie “Ang Panahon ng Halimaw” speaks about ang halimaw ng misohinismo or “the monster of misogyny”. This seems to be the only googleable occurrence of this word when spelled with an ‘h’.

There are also a few examples searchable for misoginismo spelled with a ‘g‘. For example, a post by the All UP Academic Employees Union speaking about UP Diliman’s Executive Vice President Teodoro Herbosa’s rape joke and misogyny.

Or a tweet by Salinlahi – an NGO addressing Filipino children’s needs.

Or this 2020 Facebook post by Gabriela Youth – UPLB on misoginismo at tiraniya ng administrasyong Duterte (“misogyny and tyranny of Duterte administration).

Or a primer published by IBON, an NGO that “promotes nationalist and progressive ideas”.

In a 2020 Facebook post by Gabriela Youth Laguna, Duterte is called Pambansang Misohinista or the “national misogynist”. There are a couple of instances of this word googleable spelled with an ‘h’, but there are more instances where it’s spelled with a ‘g’, as in the original Spanish spelling.

Hispanized English Borrowings and Usage Inconsistency

And then, there is this peculiar form misohinistiko, which I don’t think exists in Spanish. At least, I couldn’t find any legit use of this word in Spanish sources online. Of course I can be wrong, in which case, it would just mean that it’s a rather infrequent word in Spanish. But this does look like a case of hispanized English borrowing.

Hispanized English borrowings are a well-known phenomenon where an English borrowing is made Spanish-sounding, although there is no such word in Spanish (note, though, that the papers cited here contain some inaccurate examples where a corresponding Spanish word actually does exist: e.g., ateista ‘atheist’, incentivo ‘incentive’, etc.). Some often cited examples of such hispanized English coinages are:

Tagalog Spanish

materyalistiko materialista

kontemporaryo vs contemporaneo

dekolonisasyon descolonización

Such hybrid borrowing – where elements of more than one language are mixed to coin a new lexical unit – is actually the source for a somewhat heated discussion in the Philippine language-related discourse. So, you are going to get a glimpse of it from the following couple of paragraphs.

Dekolonisasyon was used in the theme name of the 2021 Buwan ng Wika (‘Language Month’) in the Philippines by the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (‘Commission on the Filipino Language’). This triggered another sermon by Rio Almario – the most prominent prescriptivist crusader for Filipino language consistency as defined by his personal ideas of correctness and appropriateness.

Almario labels such loans as siyokoy ‘merman’ and has been campaigning against their use like there is no tomorrow.

Breathing fire and brimstone, Almario reacted to this Buwan ng Wika theme by once again speaking of the supreme imperative to keep all borrowed Spanish and English elements in Tagalog – este, Filipino – as separate as possible, because failure to do so supposedly perpetuates colonial mentality.

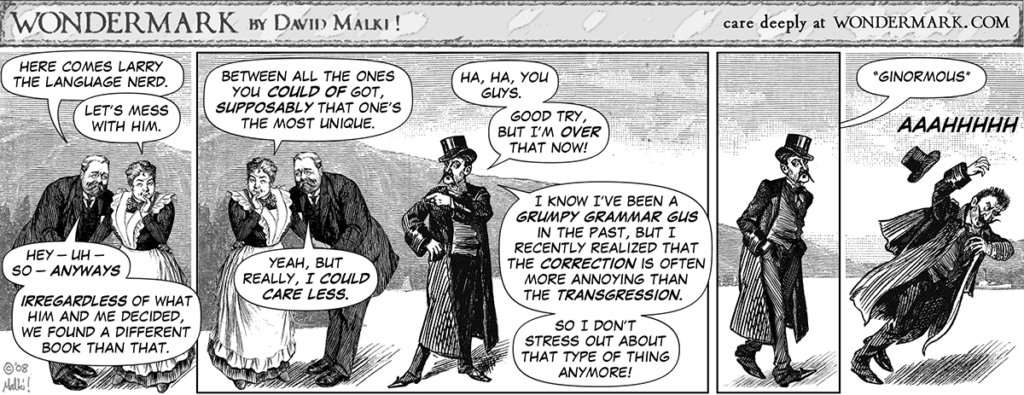

Leo Fordan’s blog post mentioned above is actually a reaction to this rant of Almario’s. It stresses – as it’s usually done by linguists in such situations – the validity of whatever words and constructions are used by native speakers in real-life situations as opposed to arbitrary prescriptivist fancy.

If you ask me, this mixing of elements from different colonial languages, if anything, reflects how Filipinos mold borrowed words as they deem fit for their needs rather then blindly following whatever is imposed on them.

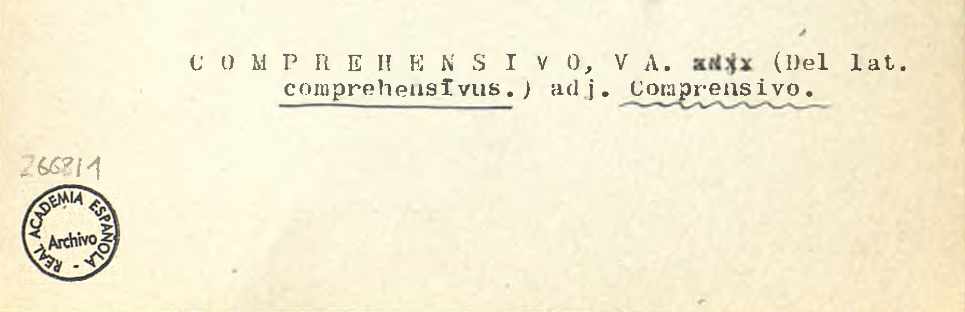

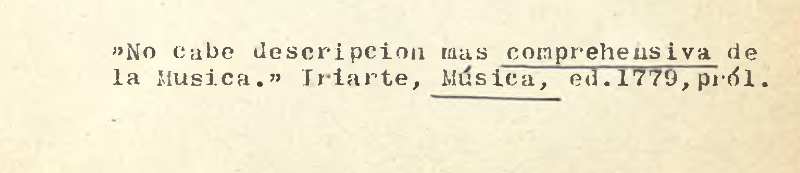

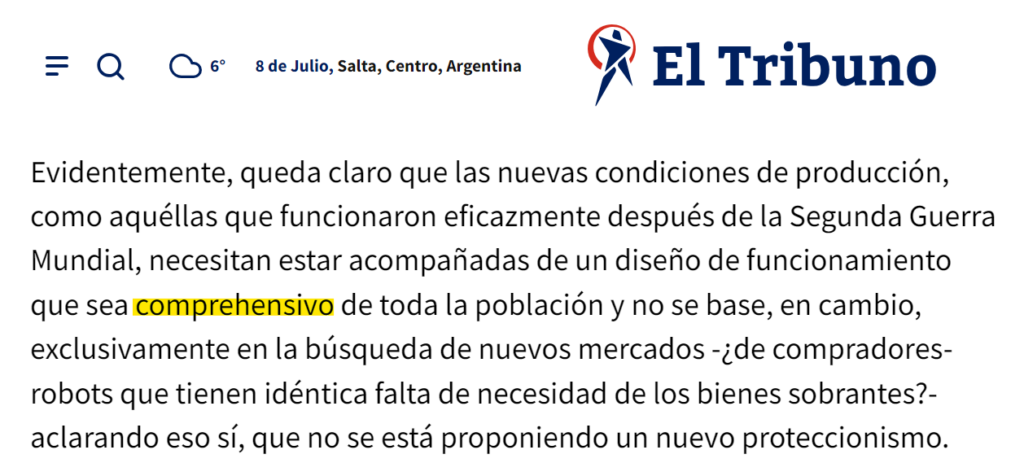

Besides, quite ironically, Almario and other prescriptivists forget that just like any other major language, Spanish has regional varieties and a long and documented history of language change, and that for the most part of the Spanish rule the Philippines was directly administered from present-day Mexico (then the Viceroyalty of New Spain). And some of the alleged siyokoy words they are so angry about actually do exist or used to exist in Spanish. For example, the Tagalog word komprehensibo is often said to come from the English comprehensive because in Spanish it is comprensivo. But, the word comprehensivo is also found both in historical Spanish sources and modern texts, such as the historical thesaurus and the Argentinian newspaper below:

Furthermore – this one might completely blow Almario’s hat off – decolonización does exist in Spanish! Look at the following examples from Mexican and Colombian newspapers:

In fact, if you go through the lists of supposed siyokoy words, you will be surprised how many of them are actually found in Spanish dictionaries, text corpora, and online periodicals.

But again, this is one of those never-ending arguments where one side relies on facts, while the other on whatever they think should be correct for whatever reason (see also this post on how some prescriptivist Filipino language teachers want you to believe that the word kila does not exist in Tagalog). So let’s leave it as it is for now and go back to the siyokoy words for ‘misoginystic’ as evidenced in actual usage by Filipinos.

Misohinistiko is used in a 2022 Facebook post of the official student publication of the college of teacher education at Aklan State University by Marielle Saballero and Thea Deann Castri. It’s worth noting that although the post is written in Tagalog, this is in Aklan (with Aklanon and other Bisayan languages most widely spoken), so potentially not exactly an authentic Tagalog speaking environment.

It is also used in the Wikipedia article on Calon Arang – a character in Javanese and Balinese folklore. But it seems to be a direct word-for-word translation from the English article, so it could be automated translation, which does not qualify as a legit example.

But misoginistiko is also used in another Wikipedia article on Lapastangang pananalita sa Tagalog – or Tagalog profanity, which doesn’t look like machine translation.

And misohinistiko is used in a 2022 Facebook post by the Calamba branch of Anakbayan (a communist youth organization):

The use of different Spanish borrowings can be inconsistent even in texts produced by the same speaker. For example, Axle Christien Tugano, a researcher from the University of the Philippines Los Baños used the word misogynistiko in his 2021 paper published in Mabini Review journal at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines. Note the spelling with the letter y following g.

In 2022, in the introduction to Pagdiriwang sa Haraya, a book on children’s poetry published by the Commission on the Filipino language, Tugano used the word misohino twice.

Again, in most cases misoginistiko is spelled with a ‘g’, not ‘h’. But interestingly with a ‘k’, not ‘c’. I’m wondering if it’s supposed to be actually pronounced as misogynistiko. It could be another case of the so-called salitang siokoy – or mermaid words – as Rio Almario calls them – that is, English words that are changed to make them sound Spanish.

In his 2024 Plaridel Journal of Communication, Media, and Society paper – Ang popularidad ng phallic jokes: Isang kritikal na pagsusuri sa mga phallokratikong pahayag ni Rodrigo Duterte sa midya, Tugano used misogynista eight times and misogynismo once.

It is not clear whether this transition from misogynistiko to misohino to misogynista/misogynismo represents self-correction, or free distribution (all these words used equally), or the author follows English in differentiating misogynist vs misogynistic, or a combination of these factors.

I wonder how the authors of the texts sampled above who used the spelling with a ‘gy’ (misogynismo, misogynista, misogynistiko) would pronounce these words. I guess, it is not impossible that these are pronounced with an affricate like in English, e.g. /misodʒɪnismo/. Which would be just a beautiful example of a hispanized English borrowing. If you have ever heard it said like this, or if this is how you say it yourself, please comment below.

Summary

To sum up, contrary to Rodel Rodis’s claim that Tagalog has no word for misogyny, Filipinos have a whole arsenal of borrowed terms at their disposal to talk about misogyny. There is not just one, but in fact, two (and a half?) Spanish borrowings, with a variety of different spellings. There is no point counting frequencies for these words, because, as mentioned earlier, there are only few occurrences online. However, it can be observed that the variants spelled with g are more frequent than the ones spelled with h.

| misogyny | misogynist(ic) | |

| Spanish | misohinya misohiniya | misohino misogino |

| Latin American Spanish | misohinismo misoginismo misogynismo | misohinista misoginista misogynista |

| Hispanized English | misohinistiko misoginistiko misogynistiko |

Apart from having a significantly rarer occurrence, the Spanish borrowings are, I would say, ideologically marked. You can notice from all the examples above that they come from discourse that is either academic or produced by left-leaning organizations. Both of which in Tagalog quite often overlap with nationalistic discourse.

The English borrowings on the other hand are much more frequent and casually used. So if you are a Tagalog learner and you’re planning to bring up misogyny in a conversation, think about things like the venue, audience, level of formality, general sentiment of your message, and so on in order to make an appropriate choice of the word. Or just use the English word, since most Filipinos will too anyway.

Concepts, Words, and Language Change

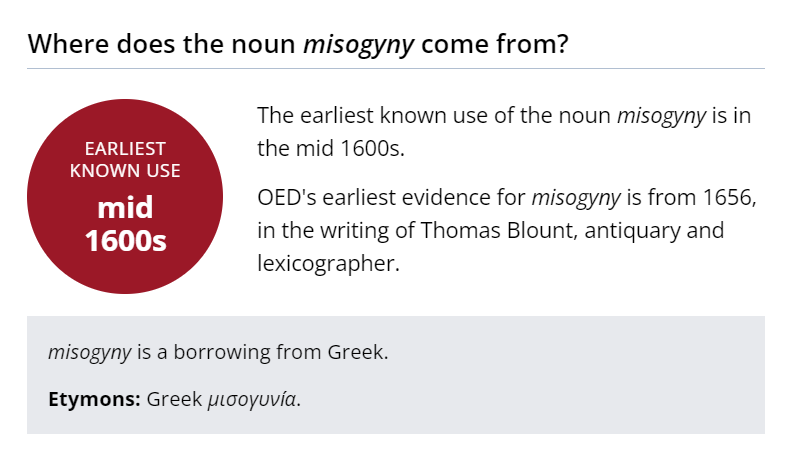

Hold on, one might say, but misohinya and misogyny are not Tagalog words. However, misogyny is not a native English word either, as it was borrowed into English from Ancient Greek. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest known use for both words is in the 17th century. Interestingly, the first known use of misogynist is actually earlier than the first known use of misogyny.

The word misogynist seems to have entered the English language in 1620.

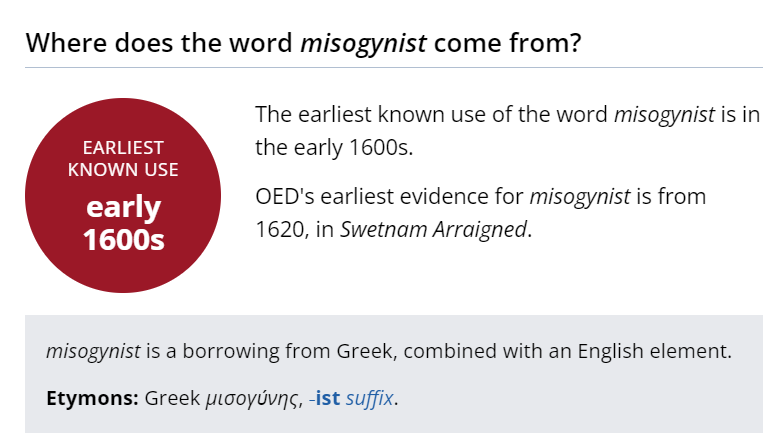

Five years before that, in 1615, an English fencing master Joseph Swetnam wrote a pamphlet titled as follows:

The arraignment of lewd, idle, froward, and unconstant women: or the vanity of them, choose you whether, with a commendation of wise, virtuous and honest women, pleasant for married men, profitable for young men, and hurtful to none.

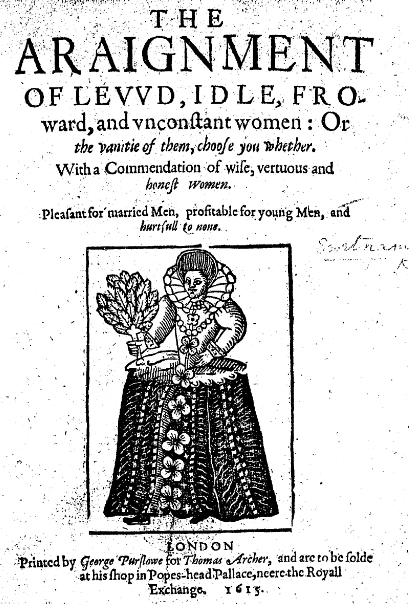

Then, in 1620, an anonymous comedy play was published under the title of Swetnam the Woman-Hater Arraigned by Women, where Swetnam was referred to as Misogynos. The play is believed to be the earliest known use of misogynist in English.

Misogyny, on the other hand, is first found in the lexicographer Thomas Blount’s Glossographia in 1656, where it’s referred to as “the hate or contempt of women”.

The language is flexible, moldable, and everchanging. It reflects the needs of its users at any given moment of time. So, if a word doesn’t exist, it does not necessarily mean that the phenomenon it refers to doesn’t exist either. It is possible that speakers of the language just haven’t felt the need to address the issue.

The absence of misogyny and misogynist in the English language prior to the 17th century does not mean that misogyny did not exist in England before that. The word was coined when someone felt the need to speak up about this phenomenon, which requires giving it a name, in order to be able to talk about it. As for Tagalog, we’ve seen that words for misogyny do exist, and misogyny is very much talked about in the Philippine society. And the current trends do present a cause for concern.

Leave a Reply