Some historians and journalists just love talking about etymology. Perhaps, it is simply due to the nature of their occupation, because they have to deal with history and with words. So, sometimes they assume that apparent similarity of words means their common history. Like when historians claim that bayanihan ‘voluntary cooperative endeavor’ might be related to bayan ‘town/nation’. Here is another case of groundless cross-language etymology propagated in modern political/historical discourse in the Philippines.

The Philippine English word salvage — meaning ‘to kill without trial’ — is often claimed to derive from the Spanish salvaje via the Tagalog salbahe.

It’s an elegant explanation. But where’s the proof?

The Popular Account

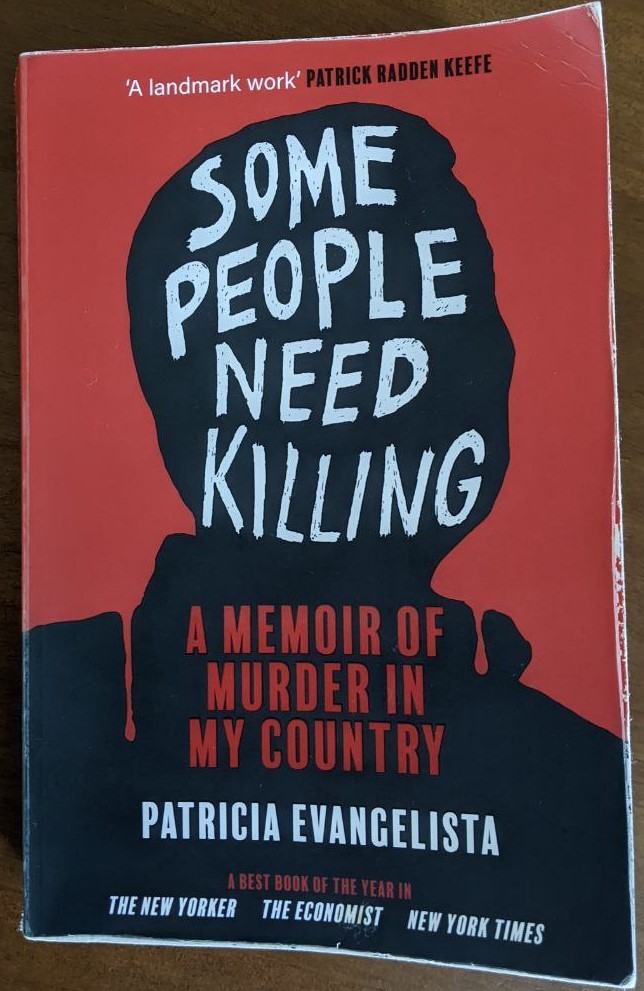

I recently came across this etymology again while reading Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in My Country by Patricia Evangelista, an overall excellent journalistic work on Dutertismo.

“In 2015 the OED appended what it called a draft definition to the official entry.

Salvage: Philippine English. “To apprehend and execute (a suspected criminal) without trial.”

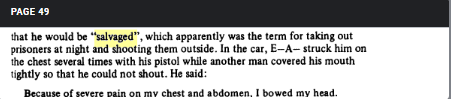

Our use derived first from the Spanish. Salvaje, an adjective introduced by the conquistadores, translated into “wild.” My people took salvaje and adapted it into our verb salbahe. “The way it is used in Filipino is different,” the historian Ambeth Ocampo told me. “Sinalbahe means that the person was savaged, not that the person was good, bad or a savage. Then we made the Spanish adjective into a verb, sinalvaje, and read it with the j into a g.”

Had martial law never been declared, salbahe might eventually have translated into its English counterpart. Sinalbahe, “savaged.” Sinasalbahe, “savaging.” Sasalbahiin, “will savage.” But the Marcoses came in the 1970s, and with them the slaughter. Salbahe was anglicized into salvage. It was a corruption, not an evolution. The poet and journalist Jose F. Lacaba attributed the translation to the “visual similarity” of the two words. Lacaba calls it and Englishing; Ocampo calls it a Filipinism.”

Ocampo himself wrote this in 2021:

“A “salvage victim” often shows signs of torture before being savagely slain, the adjective used to describe this is “sinalbahe” from the Spanish salvaje (savage). When the Spanish “j” that sounds like “he” was pronounced as “g” that’s probably how we got the term “salvage”.”

What’s Missing?

The explanation is graceful, and at first glance it makes sense. But here’s the problem — and it’s not just that Evangelista and Ocampo mix up parts of speech. Salbahe is not a verb, and sinalbahe is not an adjective — it’s the other way around. The real issue is—where is the evidence?

For this etymology to hold, you’d need proof that s(in)albahe was already in use to describe victims of state violence before salvage appeared in Philippine English (which had already happened by at least 1975.

But is there any evidence of such use of s(in)albahe?

Without a single documented case of sinalbahe used with this specific meaning prior to the emergence of salvage, this etymology collapses.

And Ocampo’s suggestion that the Spanish “j” in salbahe became /g/? Has anyone really ever pronounced it this way?

Earlier Explanations

The earlier explanations of the salvaje-based etymology of salvage do not make an explicit claim that EJK victims were referred to as sinalbahe. For example, Linguist Maria Lourdes Bautista (2000) simply pointed to salvage as a background influence:

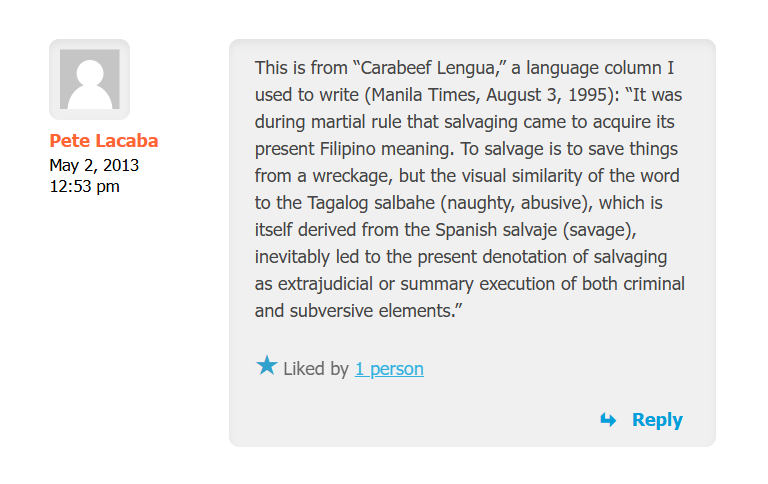

“In terms of the lexicon, S[tandard]P[hilippine]E[nglish] has changed the meaning of salvage “to save” to practically its exact opposite: to kill in cold blood, usually used when police or soldiers kill suspects before trial, i.e. summary execution – a meaning that came into existence only during the Marcos years, and found resonance because of its Spanish overtones, salvaje meaning bad.”

Jose F. Lacaba suggested the visual similarity explanation in his 1995 Carabeef Lengua column in Manila Times.

Dionisio Miranda (1992) likewise implied a retrospective link:

“Locally, “salvaged” is closer to sinalbahe (from the Spanish selvaje: wild), and it means “wildly savaged.” Filipinos seem to have a penchant for such linguistic ironies.”

Alternatives

Of course, it does look probable that some of Marcos’s butchers came up with salvage as a pun (not a corruption)—based on its phonetic similarity to salbahe. Maybe, it started as a joke about salvaging the lost souls of those salbahe who dared criticizing Apo FM. Who knows?

But even this requires objective evidence. Without it, it’s a hypothesis at best, and groundless folk etymology at worst.

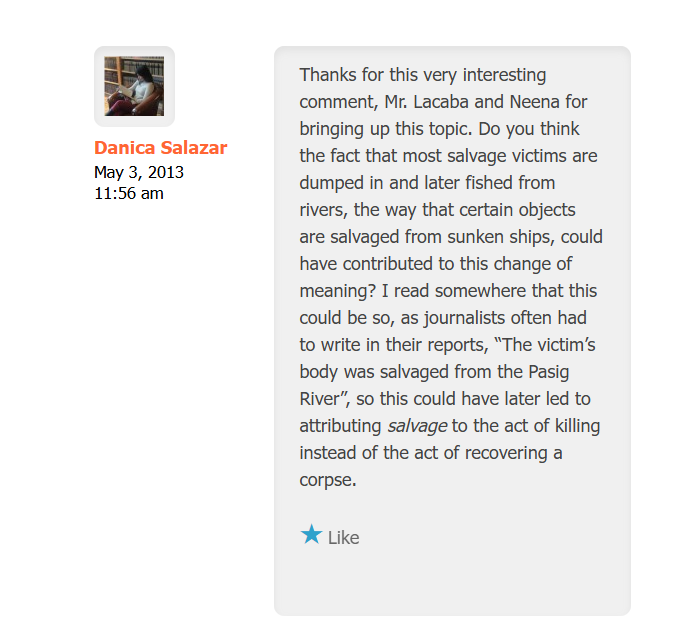

Some suggest another origin of salvage — victims’ bodies were often retrieved, or salvaged, from rivers and canals.

But again, it remains to be shown that, before 1975, there was a period of time when a series of reports came out specifically about murdered people salvaged from bodies of water before the word expanded its meaning.

And however plausible these etymologies look, until we find hard evidence, the story of salvage remains just that — sabi-sabi lang.

Di porket inulit-ulit ni Ocampo nang sampung beses, ibig sabihin totoo.

Leave a Reply